The Other Side of Picture Perfect

How tourism is transforming the UK's most beloved destinations

Down the cobbled thoroughfare, a steady flow of feet trickles in from the railway station toward the towering medieval abbey into the city centre. Honey-coloured Georgian terraces rise on either side, their elegant facades now backdrop to chaos. Arms lift skyward in unison, capturing the same Regency-era doorways and classical crescents photographed millions of times before.

By Tuesday morning, these same streets lie eerily quiet. Shop owners sweep yesterday's rubbish from beneath doorways where crowds once pressed. The symmetrical crescents stand empty, their neoclassical grandeur suddenly visible again. A lone cyclist navigates roads that, days before, were gridlocked with buses and crowded with tourists.

Within 72 hours, Bath transforms into a ghost town and back again.

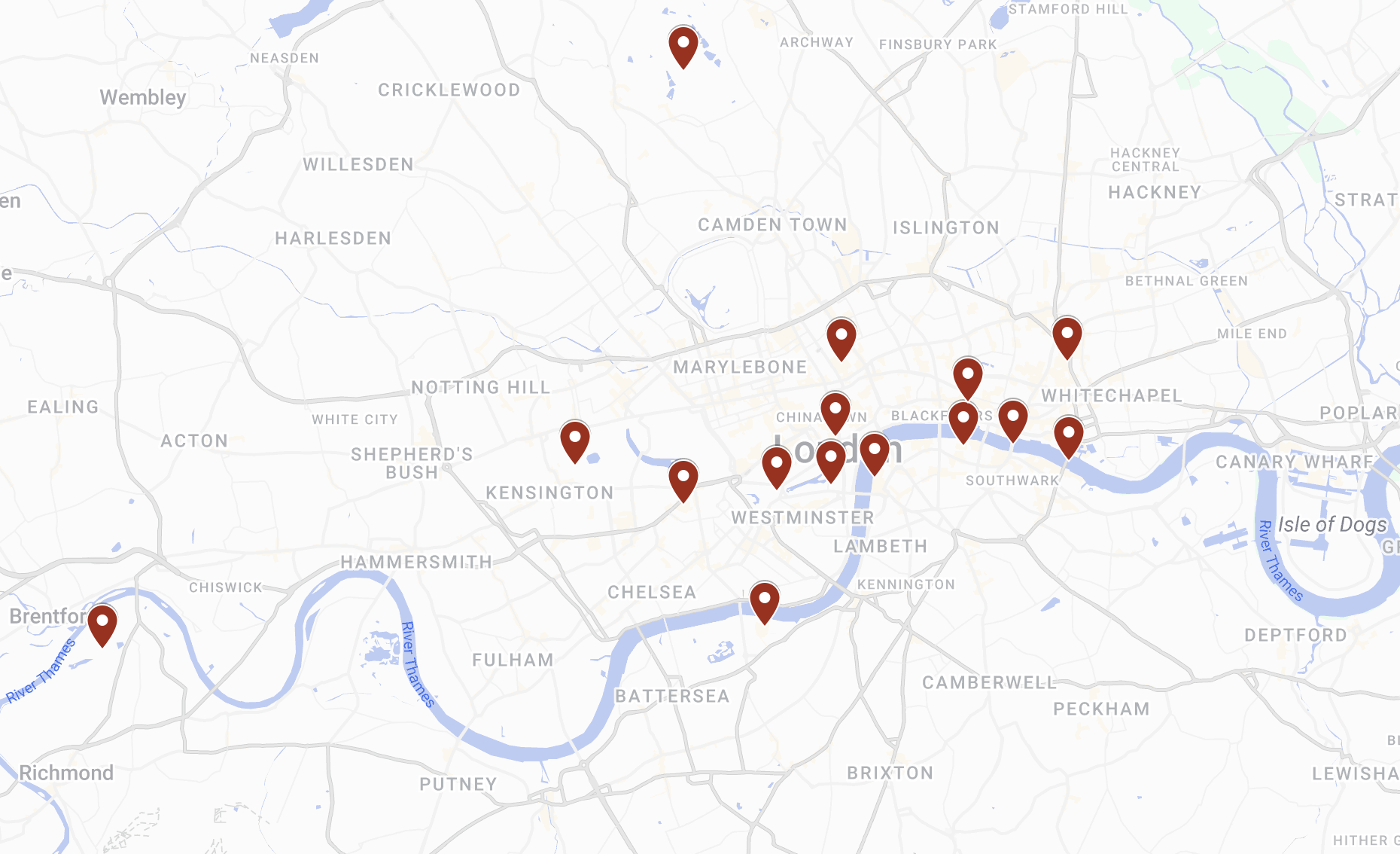

Interactive map of locations in the UK with mentions of overtourism. Created by Sydney Boyd.

The UK reached 39.2 million inbound visits in 2024, just below pre-COVID levels. As visitor numbers surge back to pre-pandemic levels, cities and towns throughout Britain are finding themselves grappling with the same pressures that sparked protests across Europe—increased housing costs, destruction of natural spaces, and infrastructure buckling under the weight of millions seeking authentic experiences in increasingly commodified destinations.

From Bath's Georgian streets overrun with day trippers to Lake Windermere choking on sewage from overwhelmed treatment facilities, the UK's most beloved places are reckoning with the true cost of their popularity.

The sustainability mirage

Are overtourism solutions making things worse?

“Whenever I hear someone say sustainable tourism now, I’m immediately very sceptical. Alarm bells start ringing. I want to know what they mean by it, because I just feel like it doesn’t really mean anything anymore,” says Dr Michael Palkowski.

Palkowski, a senior lecturer at the University of East London, says that overtourism goes far beyond empirical data–it’s a complex psychological and emotional phenomenon.

Sustainable Development in Tourism and Destination Management senior lecturer, Dr Michael Palkowski. Image courtesy of Dr Michael Palkowski.

Sustainable Development in Tourism and Destination Management senior lecturer, Dr Michael Palkowski. Image courtesy of Dr Michael Palkowski.

The psychology behind overtourism

“So overtourism as a term relates typically to destinations that are experiencing excessive amounts of tourism, and it's usually understood in a very quantifiable, quantitative type of measurement in people's heads, they tend to think of numbers, and they tend to think of capacity,” Palkowski explains. But this surface-level understanding overlooks the deeper complexity of the issue.

Drawing from the Club of Rome's 1972 "Limits to Growth" report, which famously suggests that the earth's resources can’t support present economic and population growth rates, Palkowski traces how the concept of carrying capacity started to emerge. Yet his definition is much more nuanced. “In that sense, it’s a very quantifiable idea, but it’s also something more in the sense that it’s very psychological, and sort of perceptive and emotive,” he explains. It combines excessive numbers and a psychological feeling of “too much.”

The psychological element is not always glaringly obvious. “Certain destinations will feel like there's too much tourism in terms of numbers, even if the numbers are not verifiably big,” Palkowski notes. This perception problem highlights how overtourism isn’t just about objective thresholds but about residents' lived experiences watching their neighbourhoods transform.

Palkowski, an Edinburgh-native, has witnessed firsthand how tourism can alter a city’s character. In August, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe transforms the entire city into what he describes as a “carnivalesque” atmosphere. Streets suddenly crowd with thousands of tourists. “During August, when you're walking around the city, it feels qualitatively different in terms of the time it takes to get where you want to get to, and the normal feel of the place,” he explains. The frustration became so palpable that locals began selling t-shirts with aggressive anti-tourist messages.

The management problem

Referencing Richard Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model, Palkowski explains how destinations progress through distinct stages and how poor management can lead to a destination’s decline. The changing nature of destinations over time, where souvenir shops and hotel chains emerge and begin to replace local businesses, creates a landscape that caters to tourists while alienating residents.

“I think a lot of overtourism problems are actually management-related issues,” he asserts. “There are all sorts of reasons why, maybe a lack of finance, maybe a lack of resources, etc., but it's a lack of ability actually to deal with the numbers and then to deal with the psychological problems that are emerging in the local community.”

“So, it's almost like a puzzle, and you've got all these little parts, and I think that comes together,” Palkowski says. While media coverage tends to focus on alarming statistics and anti-tourism protests, he sees a more complex picture. Quantitative pressures, psychological impacts, destination transformations, and management failures combine to create the overtourism concern: “It all comes together as one sort of big issue.”

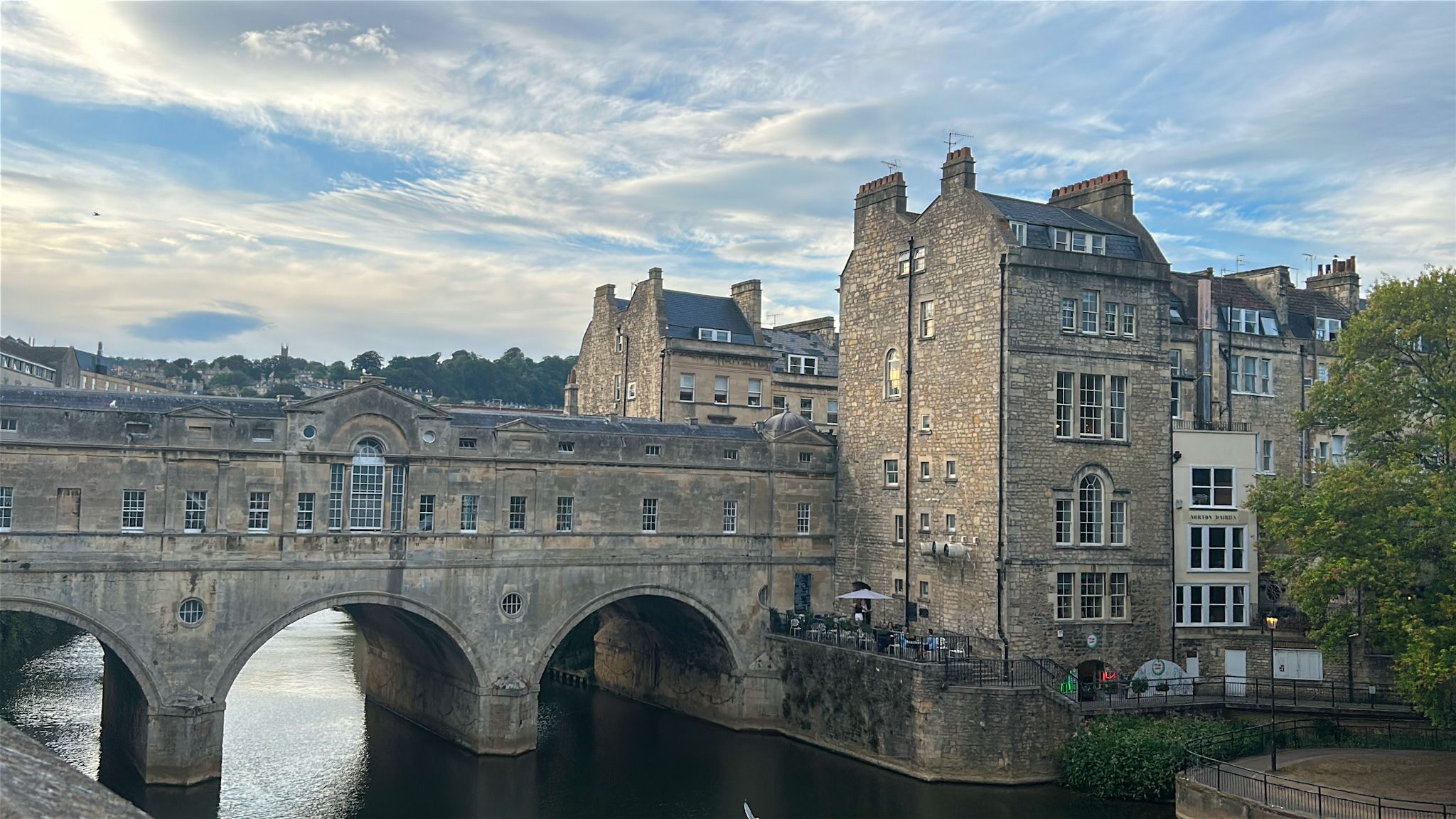

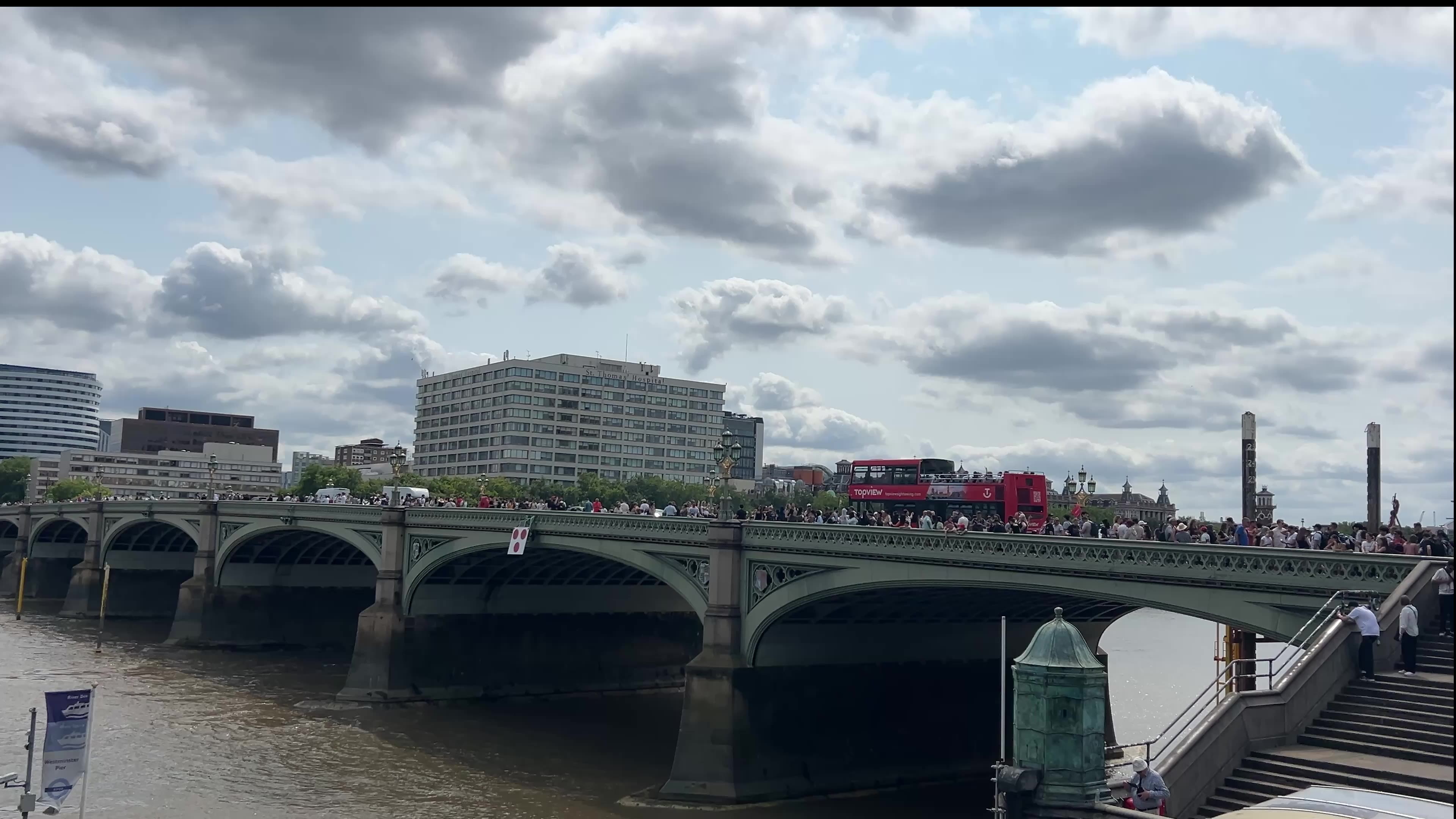

London’s exception

With over 20 million visitors in 2023, how does London handle increasing tourist numbers? Despite being one of the world’s most visited cities, London presents an intriguing situation in Palkowski’s analysis. “London is kind of different in the sense that there's been a lot of good work in trying to disperse tourists throughout the city as much as possible,” he explains. The city’s geographical advantages, with attractions spread across the boroughs, naturally encourage movement beyond concentrated tourist zones, helping mitigate overtourism.

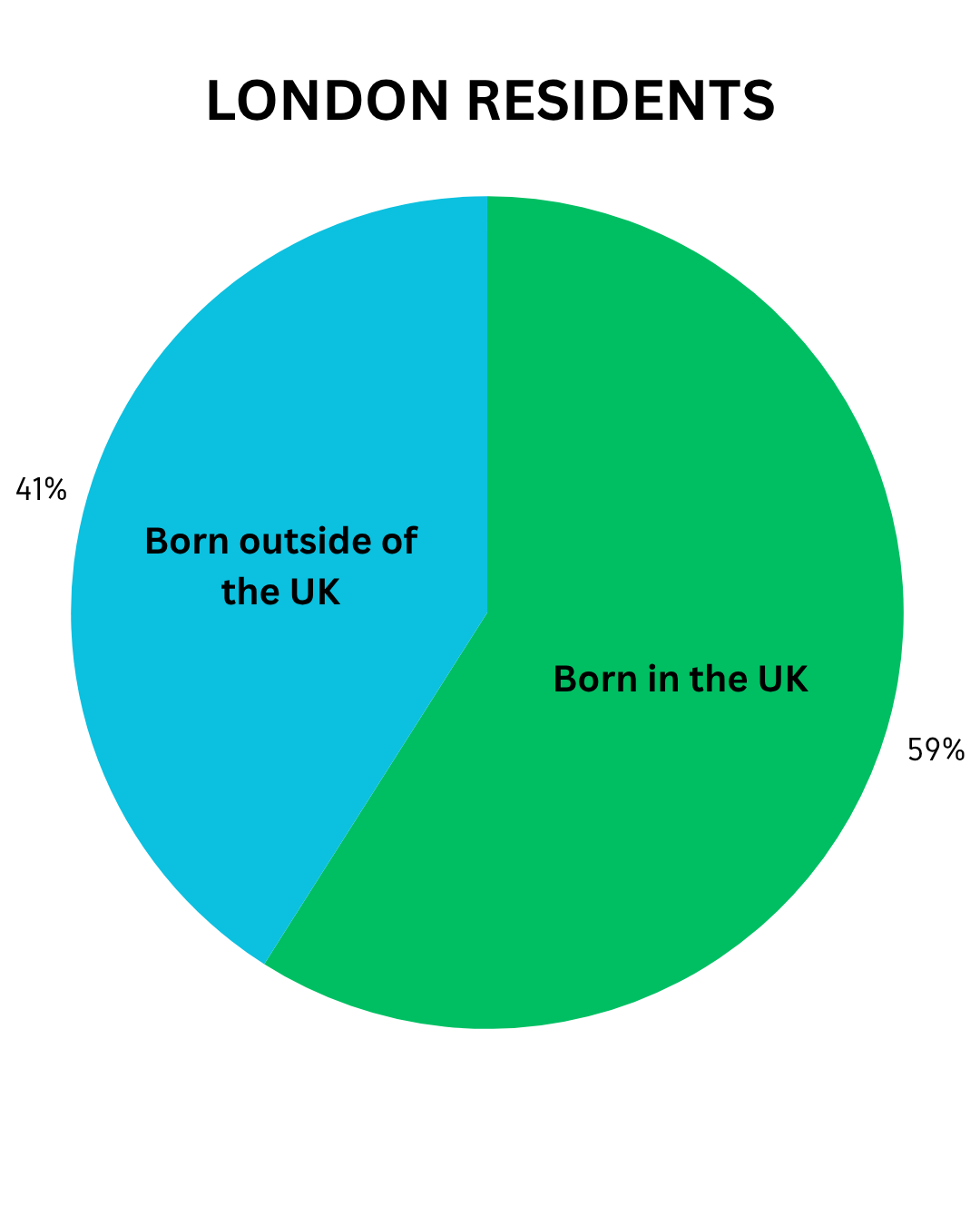

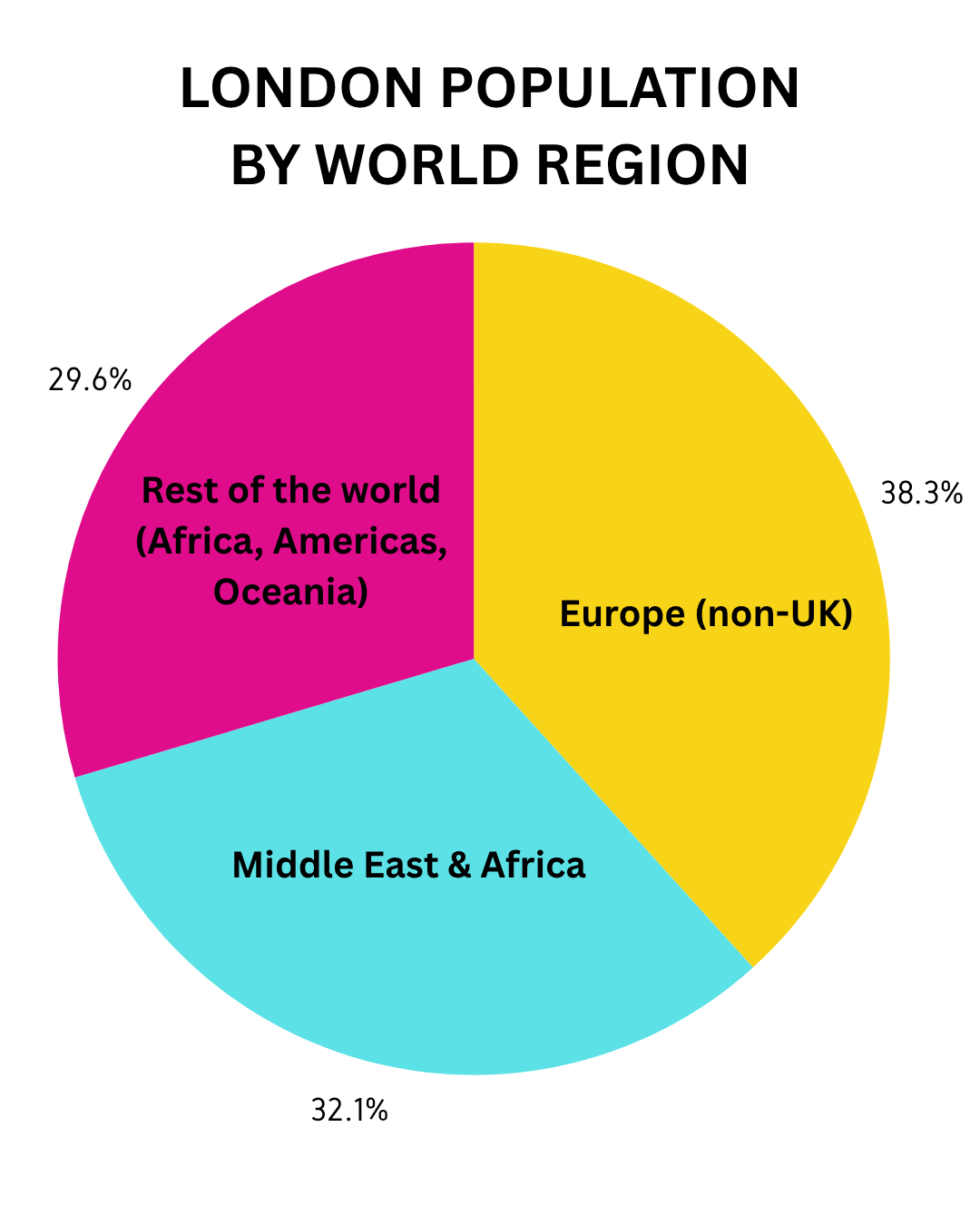

However, London’s relative immunity to overtourism reveals another layer of Palkowski’s psychological argument. The city’s demographics have shifted dramatically. According to the 2021/22 Census, approximately 40 per cent of London residents were born abroad. This “transitory, Cosmopolitan, multicultural population” means that fewer long-term residents feel the psychological impact of watching their neighbourhood transform beyond recognition.

“The feeling of overtourism, which is very psychologically based for locals, in that their place is sort of irrevocably changing,” Palkowski states. “Because such a huge amount of the people that live there weren’t born there in the first place, I think it might lead to a lack of interest within a city like London.”

He compares New York City, another top global destination, where there’s rarely a discussion of overtourism. The transient nature of these cities shields them from the same complaints that plague more immutable destinations with more stable populations.

Butler Tourism Area Life Cycle Model. Image by Barcelona Field Studies Centre.

Butler Tourism Area Life Cycle Model. Image by Barcelona Field Studies Centre.

Map of some of London's most popular tourist attractions spread across the boroughs. Image by Sydney Boyd.

Map of some of London's most popular tourist attractions spread across the boroughs. Image by Sydney Boyd.

41 per cent of London's residents were born outside of the UK. Graphic by Sydney Boyd.

41 per cent of London's residents were born outside of the UK. Graphic by Sydney Boyd.

London population breakdown by world region. Graphic by Sydney Boyd.

London population breakdown by world region. Graphic by Sydney Boyd.

“You’ve got this ongoing regulatory, surveillance-type management response that is overtaking our public spaces and making our public less liveable,”

Social media’s viral impact

Yet even London isn’t immune to the newest force shaping tourism: social media. “It’s had a huge impact,” Palkowski notes. Whereas previously hot spot locations could be anticipated, social media has reshaped that entire process due to its viral nature. “This has sort of upended a lot of that foresight and planning, because someone could post something on Instagram or an influencer could go on a destination, take a photograph, and then suddenly we get a sort of copycat ripple effect where other travellers will want to go to that location and take the same photo,” he explains.

He recounts the story of Bingley Mega Chippy, a fish and chips shop in Coventry, England. It became an overnight sensation after an AI-generated theme song went viral on TikTok. “Suddenly overnight, this chip shop in England had hundreds of people from all over the world travelling to it just to get chips and take photographs outside and do vlogs.”

This phenomenon creates what he calls “viral honey pot destinations." These locations experience intense activity before fading into obscurity when their relevance dies. He’s particularly intrigued by tourists’ attractions to seemingly mundane locations. At a California fire station, a light bulb has supposedly been burning for over 100 years. Visitors arrive by the busload to photograph the “centennial light bulb,” even purchasing souvenirs from the station’s gift shop.

The authenticity illusion

He associates this growing trend with staged authenticity. This idea was first introduced in 1973 by sociologist Dean MacCannell in his paper: “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Spaces in Tourist Settings.” Drawing on his research, he explains how destinations manufacture artificial experiences that feel authentic to tourists.

“Tourist destinations and tour operators recognise that you as a tourist want an authentic experience,” he explains. “What they do is deliberately stage various things within the destination to make you feel as though you’ve had that authentic experience, when actually… You haven’t at all. It’s completely and utterly simulated and fake.”

The examples are striking. Thailand’s floating markets, created solely for tourists and seldom used by locals, and elaborate tribal dances in Kenya are performed purely for tourist entertainment. Palkowski explains that over time, the destinations forget these experiences were artificially created, leading to a unique situation where tourists and locals believe in the authenticity of something entirely fabricated.

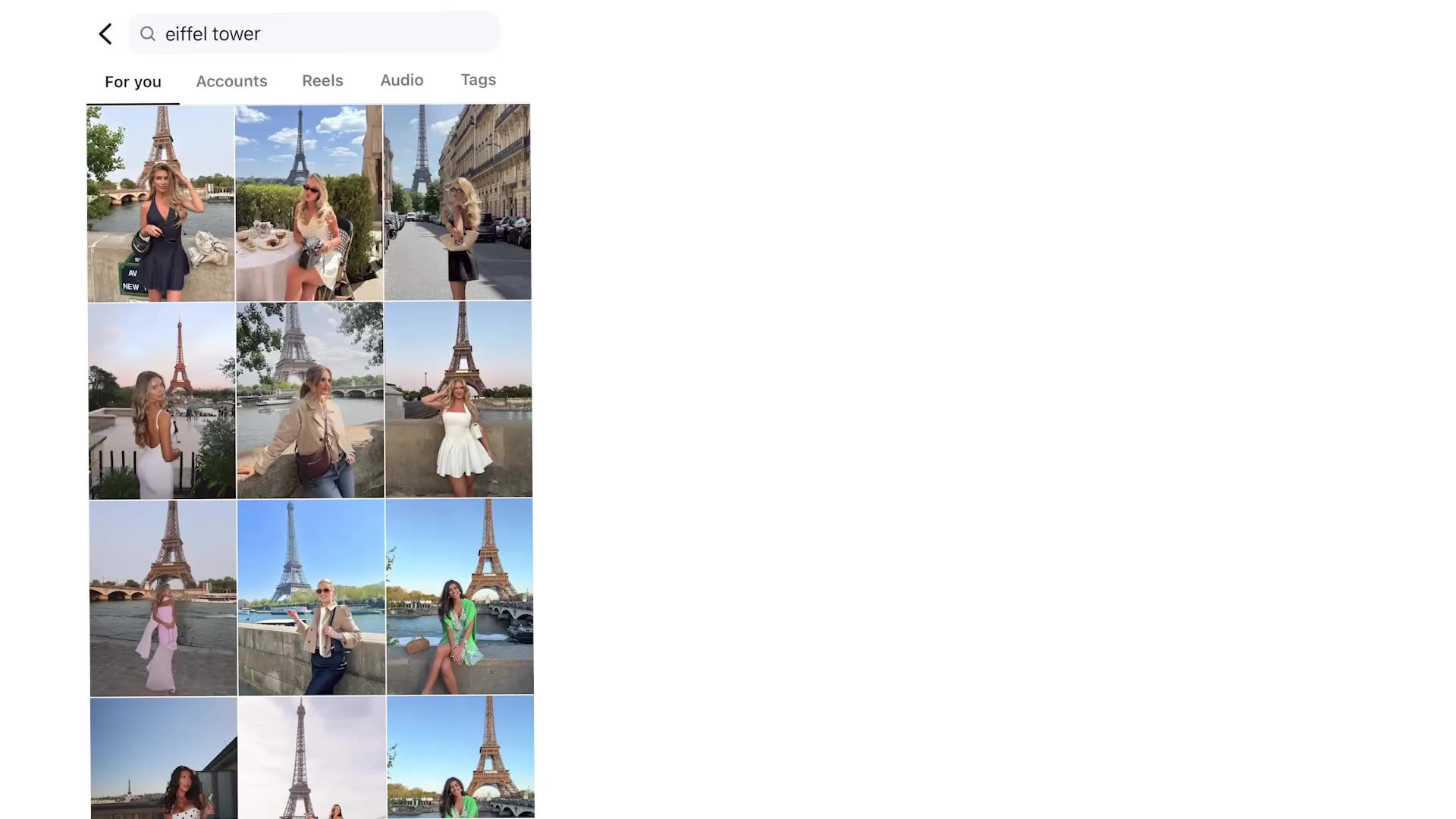

“I'd say destinations are sort of losing a lot of their real, authentic character in this crude organisational marketing and business strategy,” Palkowski asserts. “I’d say because of social media, it’s even worse now because it mandates that you get the appropriate photographs and locations that you can share on social media, notably with you now in the photograph.” Tourist photography has evolved from capturing places to capturing oneself in places. “We would normally take photos of objects, like this is the Eiffel Tower. This is my photograph of the Eiffel Tower. But now, we're always in a photograph of the Eiffel Tower. So, we're almost more important than the actual destination itself.”

The dangerous “solutions”

But Palkowski’s most urgent concern isn’t overtourism itself. It’s the solutions being proposed to fix it. His latest research, co-authored with Dr Henrik Linden, serves as what he calls “a warning” about the dangerous precedents being set in destination management.

“Tourism destinations throughout the world, in response to overtourism, are enacting very punitive and regulatory types of control in a destination,” he explains. Venice has introduced a system that requires tourists to obtain QR codes for specific access at designated times. Other cities are implementing what he describes as “surveillance and border checkpoints” in public spaces.

“You’ve got this ongoing regulatory, surveillance-type management response that is overtaking our public spaces and making our public less liveable,” Palkowski says, clearly disturbed by the implications. “You don’t want to walk around your city, and checkpoints check to see that you’re eligible to be in that location.”

Even more troubling is the rhetoric accompanying these policies. He highlights campaigns like Miami Beach’s “Breaking Up With Spring Break” advertisements. Locals addressed tourists directly: “It’s not us, it’s you… Don’t try to apologise and come crawling back.” The messaging is accompanied by images of arrests and police activity, essentially telling visitors they’re unwelcome.

Amsterdam’s “Stay Away” campaign targeting 18–35-year-old British men was even more explicit. The videos featured images of a British man in jail with warnings about criminal records and life-changing consequences. The irony wasn’t lost on Palkowski: “I know that our entire branding and destination imaging for the past 50 years has been about weed and alcohol and as a party destination…yeah, we don’t want that anymore.”

The language, he argues, mirrors far-right rhetoric about immigration. “When we talk about immigrants in far-right populist discourse, they are described as invaders, bringing problems with them to the destination,” he notes. In the same way, destinations are now being marketed as “pristine” and “pure”, and the tourists are coming in, bringing the problems, and destroying the location.

Yet he observes a troubling double standard: “A lot of the people that promote this type of stuff, they would never accept this if we started saying that about immigrants. But as soon as it starts to be about tourists, they’re like, ‘Yeah. Tourists are the problem.”

Tourist taxes: revenue in disguise

Palkowski’s scepticism extends to the financial solutions being offered as overtourism remedies. Tourist taxes, also called visitor levies, are presented as funds for destination maintenance and investment, but they can sometimes serve a different purpose. Mexico’s newly implemented tourism tax on cruise ship passengers- proposed in March at $42 per person- was reduced to $5 but is set to rise to $27 by 2027, with passengers charged even if they don’t disembark.

“You think, okay, where’s that money going? Is it going to help the destination?” Palkowski queries. The answer reveals the disconnect between rhetoric and reality: two-thirds of the revenue goes directly to the Mexican military, specifically for the management of ports.

He sees these taxes as revenue-generating schemes disguised as environmental protection. “Governments and local authorities are cash-strapped and have recognised this is a nice way for us to raise additional revenue that we can use for whatever we want,” he explains. “It’s just another way of raising revenue.”

The term “Trojan horse” appears repeatedly in his analysis. These are solutions that promise one thing while delivering another. For Palkowski, this represents a fundamental betrayal of tourists and residents. This creates increasingly regulated public spaces while failing to address the root causes of overtourism. “They're not actually about doing what they say, and the rhetoric around it is concerning, and I think it's only going to get worse.”

The future: more surveillance, fewer solutions

So, where does Palkowski see the future of tourism heading? He anticipates more of what he calls leveraging “the discourse and the language” of sustainability without meaningful change.

Technology, he believes, will play an increasingly prominent role. Virtual reality (VR) is emerging as what he describes as “a kind of proxy marketing tool.” Tech startups across Europe are developing what could become “blended, virtual, physical” tourism products within the next 10-20 years.

“London will kind of have a virtual kind of location as well that will be leveraged,” he predicts. “Some people argue that's sustainable, right? Because it could potentially prevent some people from travelling. I disagree with that. I don't think that's going to be the case.”

His scepticism about VR as a tourism substitute reflects his broader critique of technological solutions that promise sustainability while potentially creating new problems. Rather than reducing travel, he sees VR as another layer of tourism marketing that will likely increase rather than decrease demand for physical destinations.

The numbers support his pessimism about declining tourism. The UK continues to see growth in visitor numbers, driven partly by what he calls "revenge travel." A post-COVID phenomenon, people restricted due to lockdowns are now travelling more extensively than before.

"There are more people who are travelling now than before, and many of those people come to the UK, and many of those people come to London, and I don't see that declining," he notes. "If anything, I think it will increase, which will just present more challenges for the topics we are addressing."

A warning for the future

For Palkowski, this represents a troubling trajectory. Increasing visitor numbers combined with increasingly retaliatory policy responses, wrapped in the language of sustainability. His research suggests that without fundamental changes in destination management, the future of tourism may involve more surveillance, more hostile rhetoric, and more Trojan horse solutions.

As destinations worldwide grapple with the challenges of mass tourism, Palkowski's work suggests the answers lie not in disciplinary measures or surveillance systems. However, in understanding the complex psychological and social dynamics that turn a place from a home into a stage, His research serves as both an analysis and a warning. By rushing to solve overtourism, we risk creating something far worse than crowded streets.

Scars on the landscape

The Lake District's environmental emergency

England's largest lake is dying. A BBC investigation revealed that over 140 million litres of untreated sewage were illegally poured into Lake Windermere between 2021 and 2023. Not through industrial negligence, but because the Lake District's infrastructure cannot cope with the 18.11 million visitors who descend annually on the region.

Stretching over 17km and holding 300 billion litres of water, Lake Windermere sits at the heart of England's largest national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. What should be a pristine showcase of natural beauty has become a casualty of its popularity. According to Save Windermere, United Utilities, the Lake District’s sewage and wastewater management company, discharged untreated sewage into Windermere for 6,327 hours in 2024 alone. That's equivalent to 264 days of continuous raw sewage flowing into England's most famous lake.

Spillage data taken from Save Windermere. Screenshot by Sydney Boyd.

Spillage data taken from Save Windermere. Screenshot by Sydney Boyd.

The impact is immediate and visceral. Despite being in Windermere, just a short walk from the lake's shores, a resident and ice cream shop worker advised against swimming in the waters that draw millions of visitors. “If you want to go swimming in one of the lakes, I'd recommend heading north to Ullswater instead,” she suggested. “Lake Windermere just isn't safe anymore.”

The invisible burdens

A report commissioned by Friends of the Lake District, a charity dedicated to protecting the region's landscape and communities, identified numerous “invisible burdens” of overtourism. “Who Pays for the Lake District”, written by sustainable tourism expert Dr Davina Stanford, identified these issues and examined how they affect the Lake District.

One of these burdens is sewage discharge into lakes and rivers. During periods of heavy rain, sewage companies are legally allowed to discharge untreated wastewater through sewage overflows to avoid flooding. This pollution can cause harmful algae blooms, leading to severe oxygen depletion in the water. Combined with sunlight blockage and toxin release, it creates significant ecological damage and habitat destruction and kills fish.

Rushing waters of Stock Beck in Ambleside after a heavy rain eventually leading to Lake Windermere. Video by Sydney Boyd.

Rushing waters of Stock Beck in Ambleside after a heavy rain eventually leading to Lake Windermere. Video by Sydney Boyd.

According to Love Windermere, a partnership of nine organisations: “The population living around the lake can double between winter and summer, putting an extra load of nutrients into septic tanks, wastewater treatment works and sewage facilities at campsites.” The existing infrastructure was built for the 39,000 people who live permanently within the National Park boundaries. These sewage treatment facilities were never designed to handle waste from the millions of visitors.

On March 10, Environment Secretary Steve Reed pledged to ‘clean up Windermere’ and end the sewage discharges into the lake. “As part of our Plan for Change, the Government is committed to cleaning up this iconic lake,” he announced. Additionally, United Utilities is investing £230 million in upgrading nine wastewater treatment works in Windermere.

However, sewage represents just one aspect of a broader environmental crisis that often goes unnoticed by visitors. Friends of the Lake District acknowledges that while formal monitoring is challenging, the evidence of damage is mounting: “Fly-camping, littering, environmental damage from fires and barbecues, tree damage where people have chopped trees down to burn etc. are increasingly evidenced on social media, but there is no hard data kept on this by the Park or by others such as National Trust Rangers.”

The group also highlights how tourism pressure is driving harmful development patterns. “We would also argue that increased development of holiday accommodation (of all types, from pop-up campsites and re-modelling of traditional homes to create large modern ‘party houses’ to extensions to major hotels) is an environmental harm resulting from high visitor volumes and changes in visitor trends,” they explain. The scale of this issue has prompted them to commission independent monitoring.

Beyond accommodation, the sheer volume of vehicles brings its own set of problems. As Friends of the Lake District points out: “Another environmental harm relates to the impact of all the cars associated with high visitor numbers – again, this can range from the visual impact and air pollution to the churning up of roadside verges and common land and physical damage to dry stone walls and traditional buildings.”

The Lake District’s 29.2 million visitor days (spending more than three hours) equate to an additional population of 80,000 per day, and visitor numbers aren’t expected to decline. According to Policy 18 of the Lake District National Park Local Policy, tourism modelling of visitors to the area suggests a year-by-year increase of 2.5 per cent. These environmental pressures will only intensify with these figures, and no current solution appears to combat the invisible burdens.

Footpath erosion and fixing the fells

The ecological damage extends far beyond its waterways. Across the fells that define the Lake District's iconic landscape, the physical toll of millions of footsteps is increasingly apparent. Popular walking routes that were once narrow paths have transformed into highways of compacted earth and exposed stone. The footfall in the Lake District skyrocketed in 2020 due to COVID-19 lockdowns, where many sought relief in the national park.

The iconic fells experience severe degradation due to the millions of pairs of walking boots on these paths. The erosion is also driven by rainfall and the gradient of the path, or how steep the slope is.

Since 2001, the organisation Fix the Fells has been working to sustainably repair the damage to the Lake District National Park caused by erosion. This partnership programme between the National Trust, Lake District National Park Authority, Natural England, Friends of the Lake District, and the Lake District Foundation requires around £500,000 annually to fund its work repairing and maintaining 344 upland paths covering 661km. This work, however, is partially carried out by a team of dedicated volunteers.

After completing the Wainwrights in 2015, the 214 fells described in Albert Wainwright’s seven-volume “Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells”, Mark Dakin wanted a continued reason to return to the area. Sheffield-based Dakin joined the volunteers that same year. “The volunteer programme is basically self-administered by volunteers,” he says, “which is one of the attractions of doing it.”

Fix the Fells volunteer Mark Dakin over Grasmere. Image by Mark Dakin.

Fix the Fells volunteer Mark Dakin over Grasmere. Image by Mark Dakin.

In 2024, 140 volunteers contributed 3,029 unpaid days of working on the fells, with 60 per cent of those dedicated to path maintenance. The volunteers have two main work types: path maintenance days and work parties.

Path maintenance days involve clearing the drains with brushes and shovels to remove water from the path and ensure the drain remains effective. “Once water gets on a path, if it’s not shed to the side, then it just gathers pace and takes more and more material with it,” Dakin explains. Depending on the severity of path erosion, a path might be worked on every two or every 12 months, or any range in between.

The second type of work they do is work parties. This tackles heavier tasks like stone-pitching (setting large stones into the ground, creating camouflaged steps), installing new drains, and landscaping to make the path more attractive and accessible. Working in teams, these sessions are usually supervised by one of the National Trust rangers.

Much of the volunteers’ efforts are designed to encourage people to stick to the path, an effective way to limit the scale of erosion. “Even though they're wearing waterproof boots, they [hikers] don't like walking through puddles or mud,” Dakin explains. “When they get to a puddle on a path, they go around the sides, and then you see these things spreading out, and it all turns to mud, then people go wider and wider. This is how you end up with a visible scar.”

Muddy path up Loughrigg Fell. Image by Sydney Boyd.

Muddy path up Loughrigg Fell. Image by Sydney Boyd.

“It starts with what we call pigeon-holes,” he continues. “Walkers going up the same line will produce patches one after the other. Then water gets into it, creating a channel, and then a gully forms, and it just erodes like that.”

“Once you get a gully deeper than 30cms, it's always quite narrow. People don't like walking there because the grass brushes the tops of their boots and ankles. So, they walk to the side, and then it just widens and widens.” In response, volunteers might do subtle landscaping to make the main line more inviting or even cut away banks and block shortcuts to keep footfall contained. “What we do is designed to keep people on a sustainable line, even if that means moving the line onto something that will be more stable… then that’s what we do.”

A before (2004) and after (2019) of path repair on Silverhow. Image by Fix the Fells.

A before (2004) and after (2019) of path repair on Silverhow. Image by Fix the Fells.

Dakin notes that two or three volunteer-led projects usually run all season. “There might be 10 or 12 bits that we want to work on, and each one might take two or three days,” he says. “Over the summer, we'll slowly work our way up or down the path.”

To remain on the programme, volunteers must do 12 days of work. A retired accountant, Dakin typically does 12 days on the fells and another 20 days remotely working on analyses and other administrative tasks. The strength of Fix the Fells lies in its people. With various volunteers’ backgrounds, from accountants to lawyers to IT professionals, they each bring a unique skill set that helps improve and sustain the programme. Volunteers remodelled the website, manage the recordkeeping, and organise the calendar.

For Dakin, the most rewarding part of volunteering is that he’s helping to deal with some of the problems caused by walkers. But it’s not just about conservation. “There’s a social element to it, you meet like-minded people,” he says. “It’s just a good excuse to go for a walk, isn’t it?”

Ongoing path repair work at Loughrigg Fell. Image by Sydney Boyd.

Ongoing path repair work at Loughrigg Fell. Image by Sydney Boyd.

The scale of the challenge is evident at Loughrigg Fell, a popular walking destination that offers stunning views across Windermere and the central fells. Recent restoration works included stone pitching to help walkers navigate increasingly indistinct rocky sections. A sign of how heavy foot traffic has worn away the natural path. The improvements were designed not just to guide walkers, but to divert rainwater across the path rather than directly down the fell. This work addresses the erosion that threatens the fell's stability.

Footpath erosion also affects wildlife, fragmenting habitats and disturbing breeding grounds. It's another manifestation of overtourism reshaping the Lake District's ecology. “We do know that biodiversity remains in decline and is relatively poor across the Lake District National Park,” Friends of the Lake District explained.

“What we have at the moment is an extractive form of tourism that takes without giving back, whose profits bring little benefit to local residents, and which seems locked into the pursuit of ever more tourists.”

The economic paradox

So how is the Lake District supposed to combat these issues, despite relying on tourism's economic benefits? In 2023, the industry generated £2.304 billion in revenue, supporting thousands of jobs across the region. Tourism is the lifeblood of the local economy. Yet the very visitors who fuel this economy are slowly destroying what they came to see. The sewage crisis and footpath erosion aren't just environmental disasters. They're symptoms of what happens when tourism growth wildly outpaces infrastructure development.

Friends of the Lake District acknowledges the complexity of this challenge: “There is no silver bullet – simple measures that would have an immediate effect,” the organisation explains. “Tourism is important to Cumbria in terms of income and jobs – even if many jobs are low-paid and insecure/seasonal – while access to the Lake District is a right that should be open to all. At the same time, the negative impacts of tourism need to be mitigated.”

A regenerative future

But the organisation argues that incremental changes won't be enough. “More than seeking a slightly better balance between these interests, though, what we ultimately need is a different form of tourism,” they contend. The current model, they argue, is fundamentally flawed: “What we have at the moment is an extractive form of tourism that takes without giving back, whose profits bring little benefit to residents, and which seems locked into the pursuit of ever more tourists.”

Instead, Friends of the Lake District envisions a radical transformation: “We need to change this to a regenerative model of tourism that not only minimises harms but also gives back to the landscape.” This shift would require action from all stakeholders. “Such a paradigm shift needs a change in supply and demand. Holiday providers must operate differently, and the Lake District National Park Authority must impose and apply planning rules to make them do so. Visitors themselves need to understand that their right to access the natural beauty of Cumbria comes with a responsibility to ensure that, through their visit, the landscape is enhanced for future generations to enjoy.”

As a first step toward this vision, the organization proposes testing new approaches: “In the shorter-term, some form of visitor levy trial coupled with improved, scaled-up public transport would serve as proof of concept – that a levy can be introduced fairly and that it has a positive impact in terms of traffic levels and the various impacts due to private vehicle usage.”

Implementing a tourist tax

With mounting environmental and social pressures, there's growing support for implementing a visitor levy. The concept of a visitor levy – a tax that could fund infrastructure improvements and conservation work – is gaining popularity among local authorities and conservation groups.

The reception to such proposals has been encouraging. Friends of the Lake District reports that: “the reaction has been overwhelmingly positive: we've had supportive responses in discussions with local people and visitors, as well as with local MPs and Councillors, with many expressly in favour of some form of levy. The National Park Authority has been open to listening to and participating in the debate.”

Research suggests visitors support such measures when revenue is directed toward destination improvement and conservation. A modest levy could generate significant funds for addressing the Lake District's infrastructure deficit.

Addressing concerns that such measures might harm the local economy, Friends of the Lake District points to international evidence: “There is evidence from places that have already introduced levies that a small charge on the cost of a trip does not deter visitors. Venice's visitor numbers went up following the introduction of a charge for day visitors, and in many parts of Europe, a fee is charged as standard. Adding less than a cup of coffee to a trip to the Lakes seems highly unlikely to put anyone off coming.”

But progress remains slow. At the local level, Friends of the Lake District notes: “there are no tangible policy proposals as yet, but we are aware of, and are contributing to, policy discussions within the Lake District National Park Partnership.” However, momentum is building nationally, with “various Mayors and heads of other National Parks and regions speaking out in ‘support of a visitor levy and for a change in the law to allow local authorities to levy an overnight stay tax.’”

A couple using Lake Windermere as their photo backdrop. Image by Sydney Boyd.

A couple using Lake Windermere as their photo backdrop. Image by Sydney Boyd.

Beyond funding mechanisms, the organisation envisions broader changes to regional tourism operations. “A visitor levy would help to bridge the gaps, as would stronger policies relating to transport,” they explain. “We’d like to see greater focus on tourism activities that enable people to genuinely understand, enjoy and experience the special qualities of Lake District (rather than it being used simply as a backdrop for activities that don’t achieve this and are largely unrelated to the landscape) and for this to be in ways that create a mutually beneficial relationship between visitors and the landscape and the communities within it.”

One example they point out is the issue of developing a Zip World attraction, a zip wire tourist attraction, in Elterwater. Instead, “the quarry could be opened up for people to experience with someone from a family with quarry heritage as a guide.”

They also advocate for coordinated policy approaches: “Policies (and legislation) relating to second homes and holiday lets should also be strengthened – something we have sought for many years. Again, tourism policies should be linked with transport policies – better public transport would help residents and visitors and better protect the landscape.”

But the economics remain challenging. Tourism revenue of £2.304 billion makes the industry too crucial to the local economy to be restricted severely. The challenge lies in finding ways to reduce environmental impact without devastating the communities that depend on visitor spending. As the Lake District’s ecological crisis deepens, the challenge lies in whether radical change will come soon enough to preserve what millions come to see before the damage becomes irreversible.

Bath's perfect storm

When Netflix, MICHELIN, and Jane Austen collide

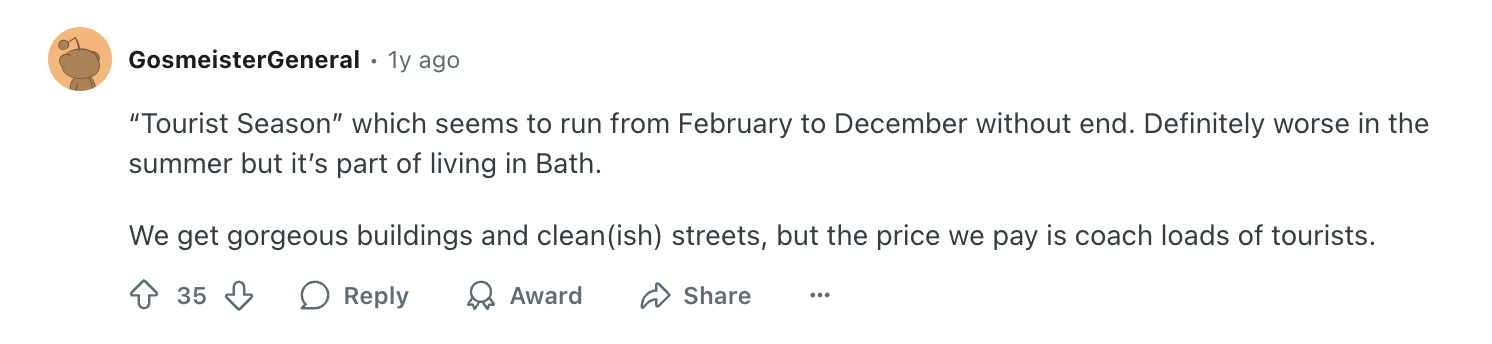

Bath, England, was scrutinised in 2023 when Fodor’s Travel, a leading travel publication, investigated the Georgian city’s tourism pressures. The publication raised suggestions of a possible tourist tax. It concluded that: “Maybe the answer sits in considering how we visit cities like Bath, when we go, how long we stay, and in what way we experience the city.”

There’s been a rise in conversations surrounding where not to travel due to overtourism. A “No List” from Fodor is published annually, highlighting destinations they recommend avoiding due to overtourism negatively impacting the local environment and communities.

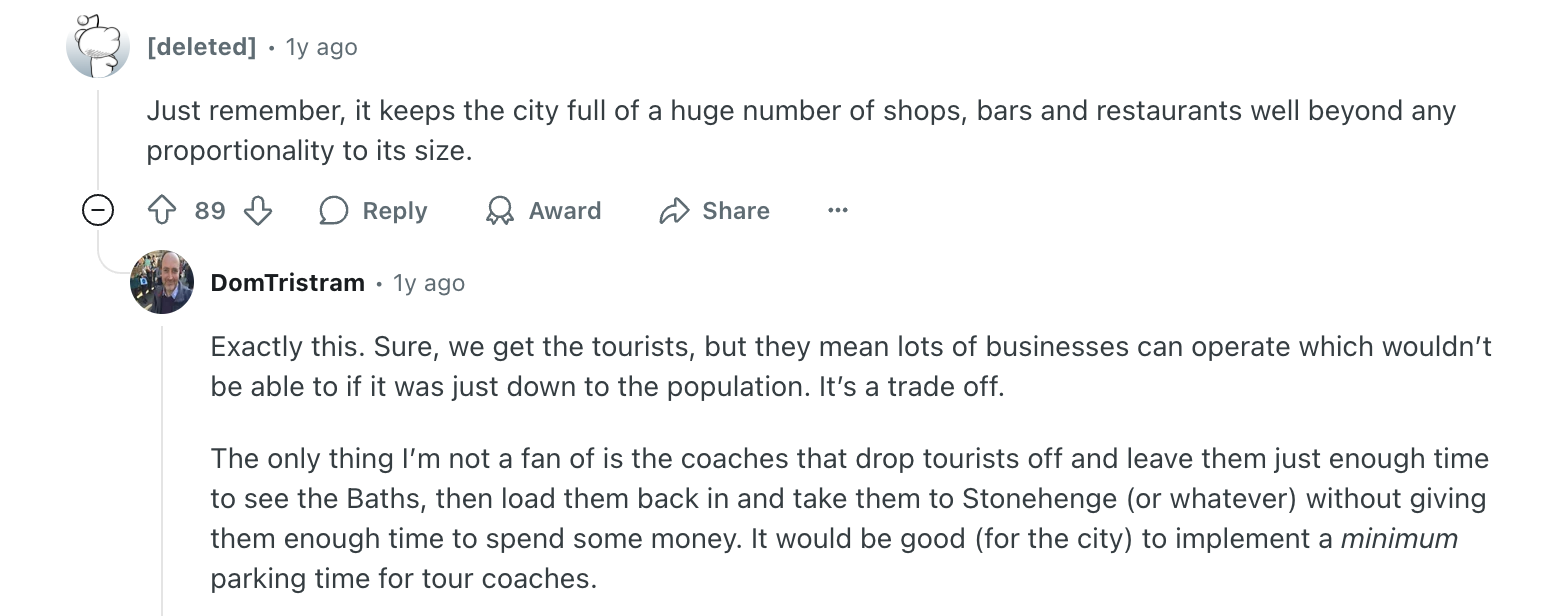

Users on Reddit under the sub “r/Bath” have echoed these concerns. Locals have complained that the city has become overcrowded with tourists, contributing to a lack of affordable housing and inadequate transportation services—familiar complaints in popular tourist destinations across Europe.

However, Kathryn Davis, Chief Executive of Visit West, the Destination Management Organisation overseeing Bath, Bristol, and the surrounding areas, offers a different perspective. Unlike many destinations now grappling with visitor management, she argues that tourism isn’t an imposed burden on Bath. It’s woven into the city’s DNA.

“We use the phrase ‘the original wellbeing destination’ because the whole place was built around the spa culture of the Romans 2,000 years ago,” Davis notes. Developed as a spa retreat for Georgian society in the 18th century, Bath has been successfully managing visitors for over two centuries.

Yet Bath’s tourism profile has evolved dramatically in recent years, driven by multiple intersecting factors that extend far beyond its traditional heritage appeal. The city’s literary connection to Jane Austen has long attracted devoted readers. Since 2020, Netflix’s “Bridgerton” has put Bath on the map for an entirely new audience. Season 3 alone garnered 92 million views in 2024, transforming Georgian architecture into instantly recognisable backdrops for millions of viewers worldwide.

Simultaneously, the MICHELIN Guide named Bath one of 10 “exciting foodie destinations to explore” in 2025. Add this to Bath’s position as a prime day trip destination from London, with trains arriving every 30 minutes on the 90-minute journey from the capital, and the result is over 6 million annual visitors contributing around half a billion pounds to the local economy.

The timing couldn’t be more significant. 2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. Events have been taking place throughout the year in her honour, culminating with the Jane Austen Festival in September and her actual birthday celebrations in December. These are expected to attract thousands of additional visitors. For a city already managing the intersection of wellness tourism, media-driven visitors, and day-trip accessibility, the anniversary represents another draw for an already complex tourism landscape.

Bath is no stranger to what Davis describes as the “feast or famine dynamic,” but how is the city expected to handle these converging factors that suggest growing tourist numbers ahead?

Reddit posts under r/Bath. Screenshots by Sydney Boyd.

Reddit posts under r/Bath. Screenshots by Sydney Boyd.

Kathryn Davis, CEO of Visit West. Image courtesy of Visit West.

Kathryn Davis, CEO of Visit West. Image courtesy of Visit West.

Floral display for Jane Austen's 250th Anniversary in Bath City Parade Gardens. Image by Sydney Boyd

Floral display for Jane Austen's 250th Anniversary in Bath City Parade Gardens. Image by Sydney Boyd

The day trip appeal

Bath's appeal as a day trip destination isn't accidental. Great Western Railway run services roughly every 30 minutes during regular operating hours, creating what Davis describes as “substantial capacity coming in." Combined with Bath’s position as the furthest point from London a coach driver can legally travel before turning back, the city's role was cemented the natural endpoint for the classic "Windsor-Stonehenge-Bath" tourist circuit.

The scale of these organised day trips is staggering. Viator, a popular marketplace for travel experiences, currently offers 47 different day trip options from London. These range from the popular “Stonehenge, Windsor Castle and Bath Coach Tour” to dedicated “Stonehenge and Bath Day Trip” packages. Get Your Guide lists 21 “London to Bath Day Trips,” while other major tour operators contribute dozens more options. This creates hundreds of weekly organised tour departures.

The reality of these compressed visits is apparent in experiences like Avery Goldberg’s. A London-based visitor, she had about “an hour or two in Bath” during a day trip from Viator in March. This time constraint immediately creates a “ticking-off” mentality where visitors sample rather than truly experience an attraction: “I just walked around and looked at Pulteney Weir and the gardens, saw the Abbey but didn’t go in, and saw a few ‘Bridgerton’ filming locations.”

The economic impact of such visits is limited despite the physical presence they create. Day-trippers like Avery contribute minimally to the local economy by not staying overnight or dining extensively. They likely spend only on a light meal or snack while occupying space on the city's streets and at its attractions. “It can be a challenge, because what you’re looking at is ensuring that people are making an economic impact when they’re here,” Davis explained. The goal isn’t eliminating day trips, but ensuring “people can tolerate the challenges if they know that at the end of the day, it’s doing good to the local economy, local businesses and local jobs.”

This creates the challenging dynamic: visitors who generate relatively little revenue per person while contributing to crowding that can affect residents and higher-spending overnight guests. It also contributes to what Davis describes as a “feast or famine” dynamic of Bath’s tourism economy. This is when businesses peak during weekends and busier seasons and experience mid-week and off-season lulls. Around 60 per cent of overnight visitors are domestic and 40 per cent international. The latter tend to stay longer—averaging six days compared to 2.5—and spend more.

This has effectively created two parallel tourism economies within the city: one built around premium, longer stays in Bath’s high-end hotels, and another shaped by fleeting visits where travellers skip key attractions and spending opportunities. Bath’s compact size and accessibility by rail and coach contribute to high day-tripper volumes that are, in Davis’s words, “really difficult to control and difficult to measure.” Weather remains one of the most significant variables affecting footfall, and with little real-time data available on day visitors, managing their impact becomes a challenge. Especially when their presence is felt immediately on crowded high streets and clogged roads.

Despite these constraints, day-trippers often feel satisfied with their brief sampling. Avery “would’ve liked another hour to visit Prior Park from the 2005 “Pride and Prejudice” film adaptation and see the Roman Baths and Abbey from the inside.” But she ultimately felt that her short visit was enough.

The rise of screen tourism

Media influences are influential in driving Bath’s modern tourism patterns. The city’s appearances in “Bridgerton”, “Les Misérables”, and its association with Jane Austen and “Pride and Prejudice” create a powerful draw for bibliophiles and cinephiles alike.

The impact of Netflix’s “Bridgerton” on Bath’s tourism can’t be overstated. Season Three marked the show’s biggest opening weekend. The first half of the season accumulated 45.1 million views in its first four days, approximately 165.2 million hours of viewing time, making it Netflix’s 10th biggest English-language series. Based on the book series by Julia Quinn, Bridgerton is planned to have eight seasons, one for each book. Looking at the ratings, the Bridgerton hype isn’t expected to die off anytime soon.

Bridgerton filming in Bath. Image by Jamie Bellinger

Bridgerton filming in Bath. Image by Jamie Bellinger

This massive viewership translates directly into tourism interest. Avery Goldberg’s experience is just one testimony among many. She specifically sought out Bridgerton locations like The Abbey Deli, which is used as the Modiste in “Bridgerton”, and the Pulteney Weir, which was used to represent the River Seine in “Les Misérables.” This illustrates how film and television drive modern tourism patterns alongside the city’s established literary heritage.

For Bath’s international visitors, “the most dominant market is the United States, and about 18 per cent for all of Bath’s international market, which is high for a region.” While there’s no known direct correlation between Bridgerton and the unusually high number of Americans visiting Bath, a strong argument could be made that Shonda Rhimes’ hit television show is the culprit. The first part of Season Three led to 2.76 billion minutes of viewing time in the US.

Tour operators have rapidly adapted to capitalise on this interest. Visit Bath lists six Bridgerton-specific tours of Bath, with titles like “Discover Bath & Bridgerton with Music” and “Bridgerton Walking Tour-City of Bath Guides.” These specialised tours join the dozens of general Bath day trips, creating a new category of screen tourism alongside the city’s traditional heritage offerings.

Fred Mawer, a Bath local and professional Blue Badge tour guide for Southwest England, offers personalised walking tours of Bath, including a “Bridgerton TV/Film Tour.” One of the first to provide a Bridgerton walking tour, Mawer has conducted over 200 Bridgerton-themed tours since the show’s debut in 2020.

The Netflix series has ignited a new era of screen tourism in Bath. “Before Bridgerton, there weren't really any TV and film-themed tours of Bath,” Mawer explains. Despite the city's decades-long history as a filming location for various movies and series, screen tourism didn't exist in Bath. “Bridgerton has changed all that,” Mawer notes. “The advent of Bridgerton has meant that tour guides like me are doing dedicated Bridgerton tours, sometimes just focusing on Bridgerton, sometimes broadening them out. So, it's Bridgerton and other things filmed in Bath.” The series has created an entirely new market segment with distinct characteristics.

A tour group clustered at The Circus, Bath. Image by Sydney Boyd.

A tour group clustered at The Circus, Bath. Image by Sydney Boyd.

The Bridgerton tours “tend to be female, and it tends to be a bit younger,” with a mix of day trippers and longer stay tourists. For each tour group, Mawer adapts his approach based on interest levels. From dedicated Bridgerton fans who are “really fascinated and they want a chapter and verse about everything you could tell them about how the filming worked,” to hybrid experiences where visitors “want a little bit of Bridgerton rolled into a more general tour of Bath.”

Rather than displacing Bath's traditional appeal, the Bridgerton effect represents what Mawer describes as layered tourism. “I don't think it's changing the tourism landscape. It's just added another layer to it,” he argues. “Jane Austen tours are still a massive deal...the Roman Baths and Roman history...everyone also wants to know about the Georgian architecture. It's just another layer of interest.”

“We need to ensure that we maintain visitors and grow them where we can grow them, but not at the expense of the people who live here.”

Looking forward

So how is Bath expected to handle the converging factors that suggest growing tourist numbers ahead? For Kathryn Davis and Visit West, the answer lies in strategic management rather than visitor reduction.

Davis remains optimistic about Bath's tourism future, emphasising the city's appeal across multiple trends. “Our job is to make it resilient, so you don't have this seasonality. You squash some of those peaks and troughs,” Davis explains. Visit West is working on several campaigns to achieve this balance, focusing on spreading visitor flows more evenly throughout the year and encouraging longer stays in the city.

The day-tripper challenge remains central to Bath's strategy. Rather than eliminating these visits, Davis sees opportunity in conversion. “Day visits are still an important part of the mix, because you need them,” she notes. “This needs to run 365 days a year.” The goal is to transform brief visits into overnight stays, generating a more substantial economic impact for local businesses and communities.

Pulteney Bridge, one of Bath's most iconic sites. Image by Sydney Boyd.

Pulteney Bridge, one of Bath's most iconic sites. Image by Sydney Boyd.

The television influence shows no signs of waning either. With Bridgerton planned for five more seasons, Bath's screen appeal remains strong. Davis doesn't see the wellness trends falling out of favour either, as Bath is the only place in the UK where you can bathe in natural thermal waters. The Jane Austen appeal will also remain, with devoted Janeites continuing to celebrate the novelist with their period-themed celebrations.

Perhaps most significantly, Bath's future tourism prospects will be affected by the potential return of Asian markets. Davis explains that Chinese tourists, representing a significant portion of pre-pandemic international visitors, have been notably absent due to travel limitations. When Asian tourists return to the UK in pre-pandemic numbers, Bath could experience a substantial tourism boom, given the city's appeal to long-haul travellers seeking premium, culturally significant destinations.

The fundamental challenge remains balancing growth with liveability. “It's a living, working city with 90,000 people living in it,” Davis acknowledges. “We need to ensure that we maintain visitors and grow them where we can grow them, but not at the expense of the people who live here.”

For Bath, success will depend on maintaining what Davis calls “authenticity” while strategically managing the city's multiple tourism draws. From Roman heritage to Netflix fame to Michelin recognition. The city's tourism DNA, built over two millennia, suggests it has the foundation to handle these converging pressures. Whether it can do so while preserving the character that makes it attractive remains the defining question for Bath's tourism future.

The UK’s tourism landscape is undergoing a fundamental transformation that extends far beyond visitor numbers or infrastructure strain.

What's emerging across destinations from Bath to the Lake District reveals a more profound cultural shift in how we travel and what we expect from places. Tourism has become less about experiencing somewhere authentically and more about collecting shareable moments. Tourists now wait their turn to capture the same Instagram shot, turning historic locations and scenic landscapes into backdrop props for personal branding. This performative approach to travel, amplified by social media algorithms, is reshaping Britain's most beloved destinations in real time.

The question facing the UK isn't just whether its infrastructure can handle more tourists. It's whether the country can preserve what makes its destinations worth visiting in the first place.

Will it develop a model of tourism that enhances rather than extracts from its places? Can destinations maintain their character while satisfying the appetite for shareable experiences? Or will pursuing tourism growth ultimately destroy the qualities that draw people to the UK’s historic cities and natural landscapes?