Ink on Skin: Jiayi Chen, Artist Empowering Women Through Interactive Nüshu Performance

How did a Chinese art graduate embark on her performance career and bring the forgotten ‘women’s script’ into the British spotlight?

It was easy to spot her when she entered the room, even when we first met.

Walking into the exhibition hall, she carried a canvas bag printed all over with the word "women". Her hair was intricately woven with vibrant flower headdresses, reminiscent of Frida Kahlo. The blue and yellow curvy lines around her eyes are nüshu, echoing the sapphire cheongsam peeking out from beneath her coat.

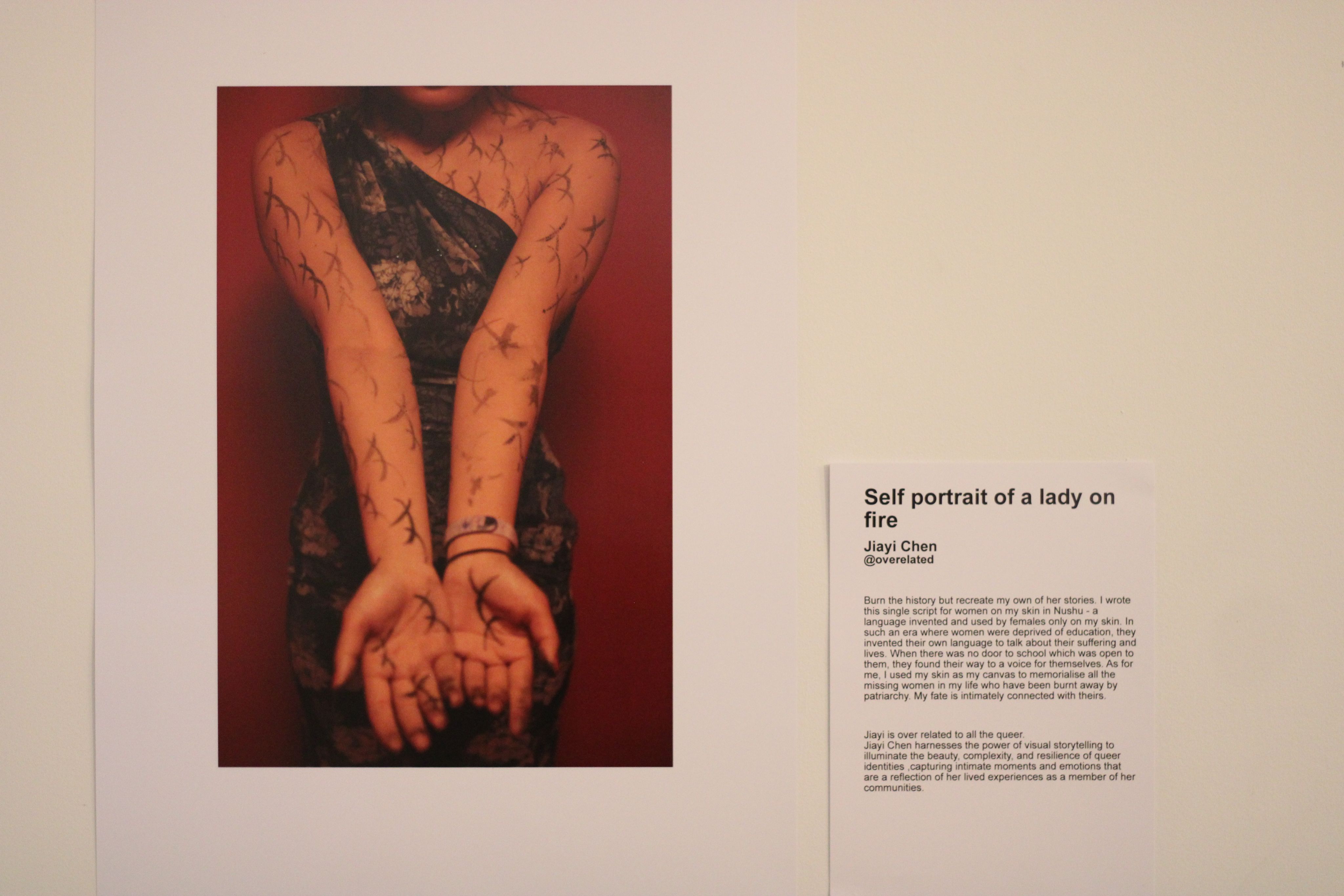

Jiayi Chen, the talented performance artist in her mid-twenties, showed up at the exhibition opening in Brighton, where one of her photographs was displayed. It was a close-up of her arms, with the character “female” in nüshu calligraphy brushed on her skin. The black ink stood out against her flesh, creating an effect that embodies strength and femininity.

Jiayi's work on display. Photograph: Xiyue Chen

Jiayi's work on display. Photograph: Xiyue Chen

“In the past, women wrote letters in nüshu to make ‘sworn sisters’ with other girls who they don’t share blood relation. They invented their own language. They wanted to be seen. They wanted to share their sufferings. They wanted to communicate.” Jiayi said. “With my hands open, I’m inviting you to be my sworn sister. Now, nüshu passes on from my palms to yours.”

Nüshu

女书

WOMEN'S SCRIPT

Nüshu, also known as “women’s script”, is a writing system created by ethnic Yao women deprived of education centuries ago in Jiangyong, a county in southern China. It served as a vital means for them to lament inequality and communicate.

As a symbol of rebellion against patriarchy, nüshu was passed down exclusively through generations of women. Awarded a Guinness World Record for the most gender-specific characters in 2005, the unique script has witnessed its revival in recent years

It wasn’t until March 2023 that Jiayi was introduced to nüshu for the first time. As a student at the Edinburgh College of Art, she was captivated by the crescent-shaped character in an exhibit. Driven by a thirst to understand its meaning and herstory (as the artist prefers over “history”), Jiayi began her nüshu study and practices.

Despite a tight schedule, the eager learner managed to snatch a field trip to Jiangyong, nüshu’s birthplace, because she wanted to “explore more about this language and make people know more in an authentic way.”

Jiayi on her field trip in Jiangyong. Photograph: Jiayi Chen

Jiayi on her field trip in Jiangyong. Photograph: Jiayi Chen

“If you master nüshu, women would respect you. They would ask you to write their biographies in nüshu because they wanted something that truly belonged to them. Their bodies did not belong to them. Women always be treated as a vessel to giving birth.”

That Thursday night was the first time I learned her name. The enigmatic artist preferred to remain anonymous on social media, and she had her reasons: “Actions speak louder than words. They know nüshu through me, but I don't want them to remember me. I want them to remember nüshu.”

Jiayi’s connection to nüshu may stem from her troubled childhood. I noticed a hint of sorrow before she said:

When I just got born, my dad's mom prepared a basket, put me inside and was ready to throw me off in the river or sell me on the market simply because I was a girl. But my mom stopped her. That's why I always focus on female, motherhood and sisterhood.

Even with a thriving career in the UK, Jiayi had to bear the pressure from her dad, who urged her to get married before 30. “I just feel very hurtful. He judges me by my age.” She grumbled.

Unlike staying low-key with her name, the artist tried her best to attract attention during her performances. By knocking on the floor, Jiayi broke the silence and captured people’s attention before introducing the script. She then covered her arms (and back, if it’s a guest artist) all over with the nüshu character for “female” using ink and brushes. Following this is a workshop where the audience could learn to write in nüshu and come home with their own artwork as souvenirs.

Jiayi and her friend wrote nüshu on each other. Video: Jiayi Chen; Editing: Xiyue Chen

Jiayi and her friend wrote nüshu on each other. Video: Jiayi Chen; Editing: Xiyue Chen

Besides her striking appearance—flower hairpins and a nüshu-embroidered belt adorned with clinking silver tassels—Jiayi chose skin as her canvas for its eye-catching effect. Sometimes, she wrote nüshu on her skin even off-stage, and it attracted curious onlookers:

“There was an old couple. They came and asked me if those lines on my forehead were the script introduced in the documentary ‘Hidden Letters’ [a PBS show about two female nüshu inheritors]. I said, ‘Wow, yes,’ and it feels so good.”

“In my recent performances, I was shocked because when I turned around, so many people stood up from their seats to get closer to see what I was doing.” Jiayi was always happy to see the interest on people’s faces.

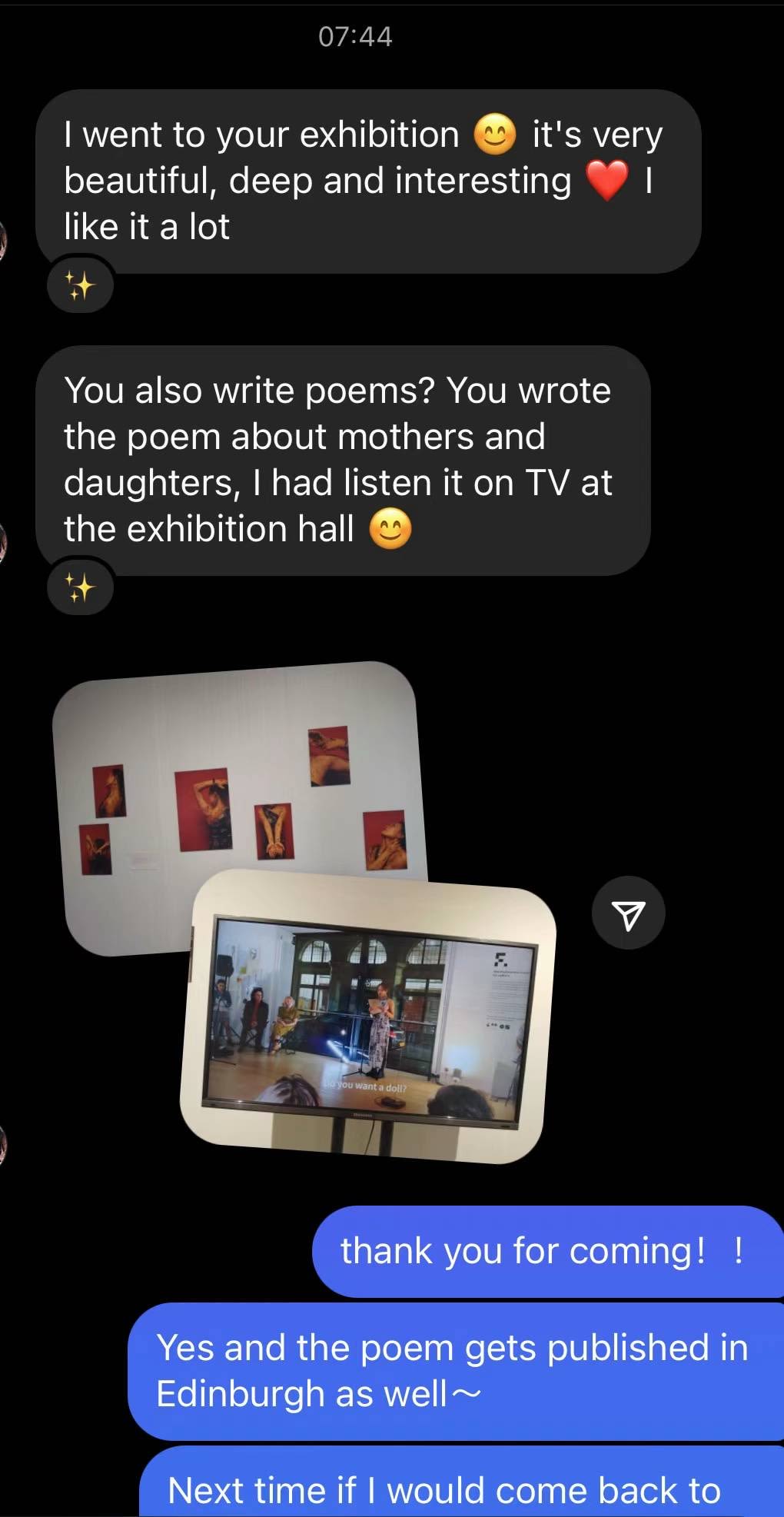

Since last September, Jiayi’s nüshu performance career has taken off. Her artworks were selected for exhibitions across the UK, drawing audiences like Phoebe Waller-Bridge and the Mayor of Sunderland. The artist was invited to perform and host workshops in over 20 cities, including Edinburgh, Stockton, Bradford, and London.

Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Make the Change, Bradford. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Make the Change, Bradford. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Screenshot of Jiayi's Instagram.

Screenshot of Jiayi's Instagram.

Jiayi at residency programme (Uprising 2023-ARC)

Jiayi at residency programme (Uprising 2023-ARC)

The Rabbit Council, Edinburgh Settlement Project. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

The Rabbit Council, Edinburgh Settlement Project. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

The Rabbit Council, Portobello Washhouse. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

The Rabbit Council, Portobello Washhouse. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

With Mayor of Sunderland. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

With Mayor of Sunderland. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Nottingham Poetry Festival. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Nottingham Poetry Festival. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

I am surprised by the popularity and acceptance of nüshu in this foreign land as she said, “Most of my audiences are from different backgrounds, and they are very supportive. My curator at Reading Riverside Museum, Dr Or, cried when she heard the [herstory behind the language]. She remembered everything I shared with her, and she shared everything with the audience.”

Jiayi's poem was exhibited at Riverside Museum, Reading. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

Jiayi's poem was exhibited at Riverside Museum, Reading. Photograph provided by Jiayi Chen.

“Some people ask me, ‘Is it allowed for foreigners to learn this language? Is it only for the Chinese?’ I said it’s a language that welcomes everyone.”

This also explains why Jiayi chose to be one of the few practising nüshu in the UK: to bring the women’s sufferings behind this secret language onto an international stage. “All my audience, they are great. No matter their gender or ethnicity. Everyone here, at least, has respect or love towards women.” Jiayi aimed to unite every voice for women she could through her practices.

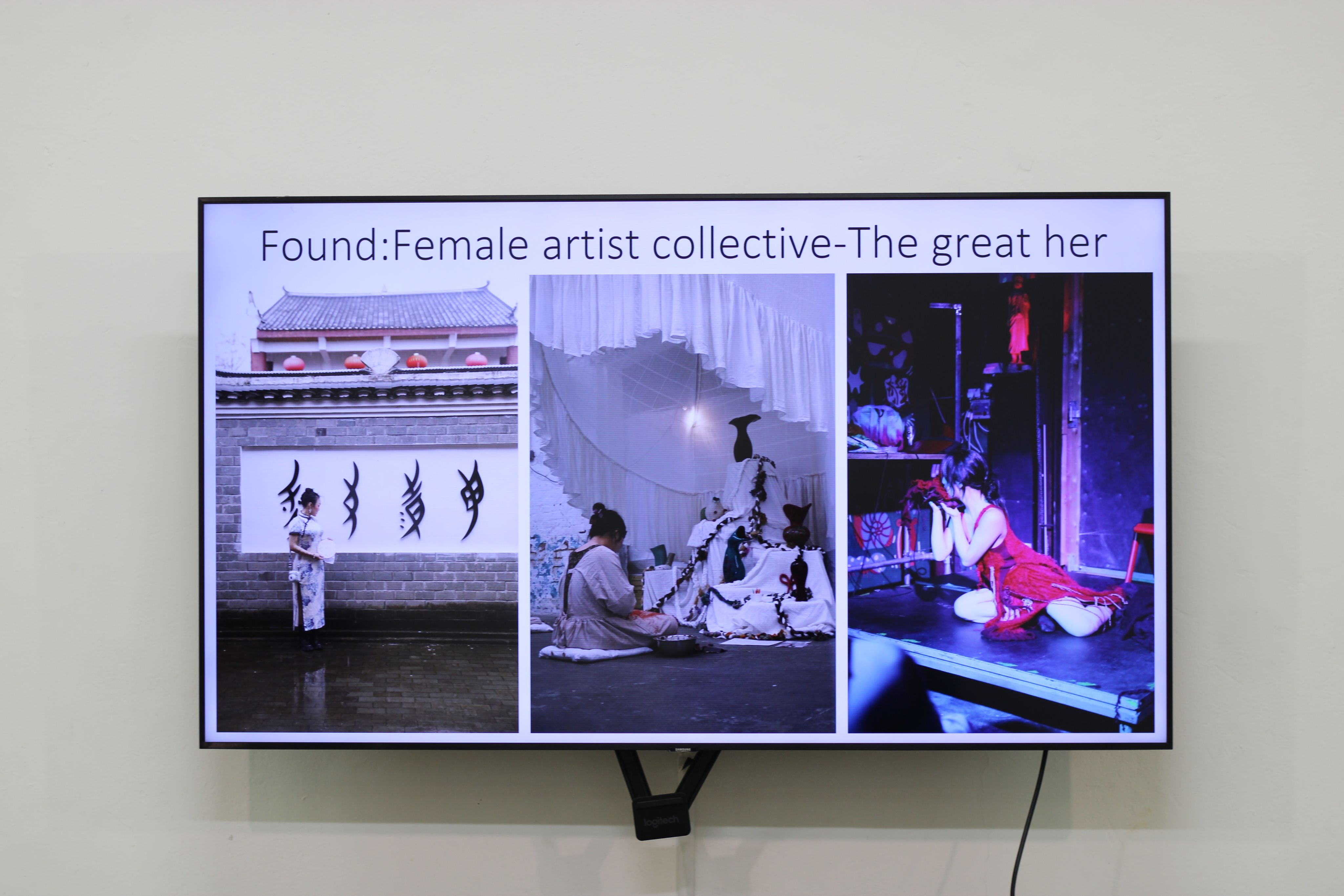

To amplify this voice, Jiayi founded The Great Her, a female artist collective. “It’s a collaboration,” She explained, “even though our art forms differ, we always support each other as if we were sworn sisters.”

Jiayi introduced The Great Her at her workshop. Photograph: Xiyue Chen

Jiayi introduced The Great Her at her workshop. Photograph: Xiyue Chen

Jiayi worked for free as she was “nourishing” her nüshu performance through her photography business. She wanted to keep nüshu as “pure” as possible. “I'm just a volunteer of this female’s language,” she said, “I would do more free workshops, and I don't want to take profit from it. I want people to know it first.”

Before her workshop the following Saturday, Jiayi asked me for my favourite motto. At the end of that event, I received an envelope featuring nüshu calligraphy that reads, “Be independent, be a lady”, a quote from Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a “great her” whom I admired. As I keep it safe on my clipboard, the promising artist arrives at her next destination with ink and brushes, ready to make her mark.