A blueprint to an auditory processing disorder

How does a person manage an unknown learning difficulty?

Those who have heard of learning difficulties can often think of a few on top of their heads.

These difficulties include dyslexia, dysgraphia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), all of which are common.

This commonality is evident when you discover that 6.3 million people have dyslexia, according to the government of the United Kingdom.

Yet, when talking about auditory processing disorder (APD) or central auditory processing disorder (CAPD), looks of confusion emerge. When describing how APD affects people, the nodding of heads occurs. It is as if people understand what those with APD are going through. In reality, they know nothing.

They won’t know the feeling of going to 15 different schools because teachers and schools don't understand their APD. That is one part of the story that KB, a creative writing university student, told when speaking about how APD has affected them. The feeling of being misunderstood is familiar among those who are neurodivergent. That is the story of Dr Sheldon A. Jacobs, a licensed marriage and family therapist from Las Vegas. APD doesn't just affect the everyday citizen. The condition also affects those who protect us: the military.

According to the British Legion “Lost Voices” report, which aims to increase the profile of service-related hearing problems, veterans under the age of 75 are three and a half times more likely to experience hearing loss than the general population. In the report, Chris Simpkins, Director General for The British Legion, said: “Hearing difficulties are one of the standout health issues affecting the Armed Forces community.” Another study found that more than half of US Army veterans suffer from APD. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs suggests auditory problems are the most common service-connected disability. Sam Rossiter, the Director of Imperial Hearing, said: “This is an issue that isn’t spoken about very often, but hearing loss among military personnel is serious and can lead to a premature end of a military career.”

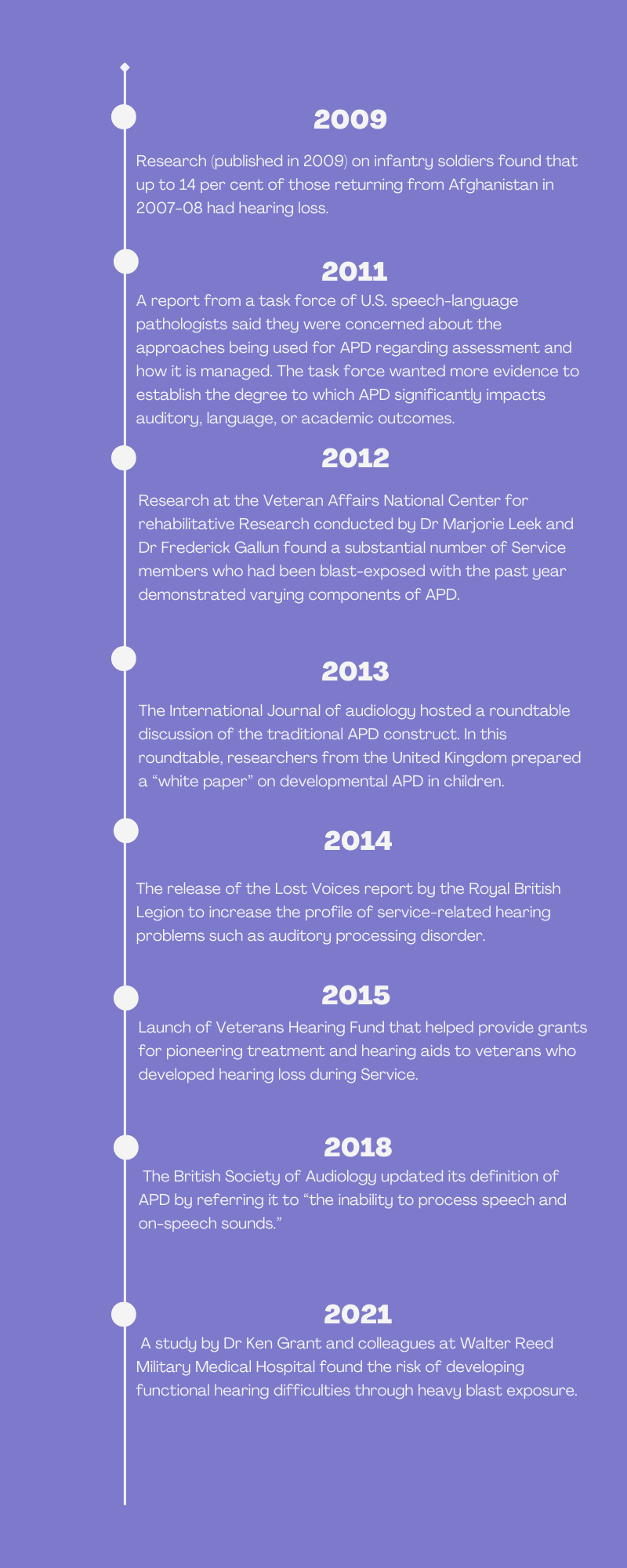

Listening to and researching these stories of how APD has affected people's lives positively and negatively resonates with the experiences that many neurodivergent people have gone through. This resonance includes me, where I was diagnosed with APD at six. The experience of being misunderstood, having self-doubts in your ability, and finding strategies to manage this difficulty is common among those who have the difficulty. On the flip side, having a learning difficulty also brings a fresh perspective on the day-to-day issues that everyone faces. All walks of life celebrate the outside-the-box way of thinking, the greater sense of empathy and increased resilience that many of those with APD have.

Speaking to those with the condition has made me realise that I wasn't the only one dealing with the consequences of having a learning disability.

These consequences include increased resilience and the feeling of being misunderstood.

Talking to experts, schools, government and those with the condition, these conversations have highlighted the nuances, issues and challenges this subject brings.

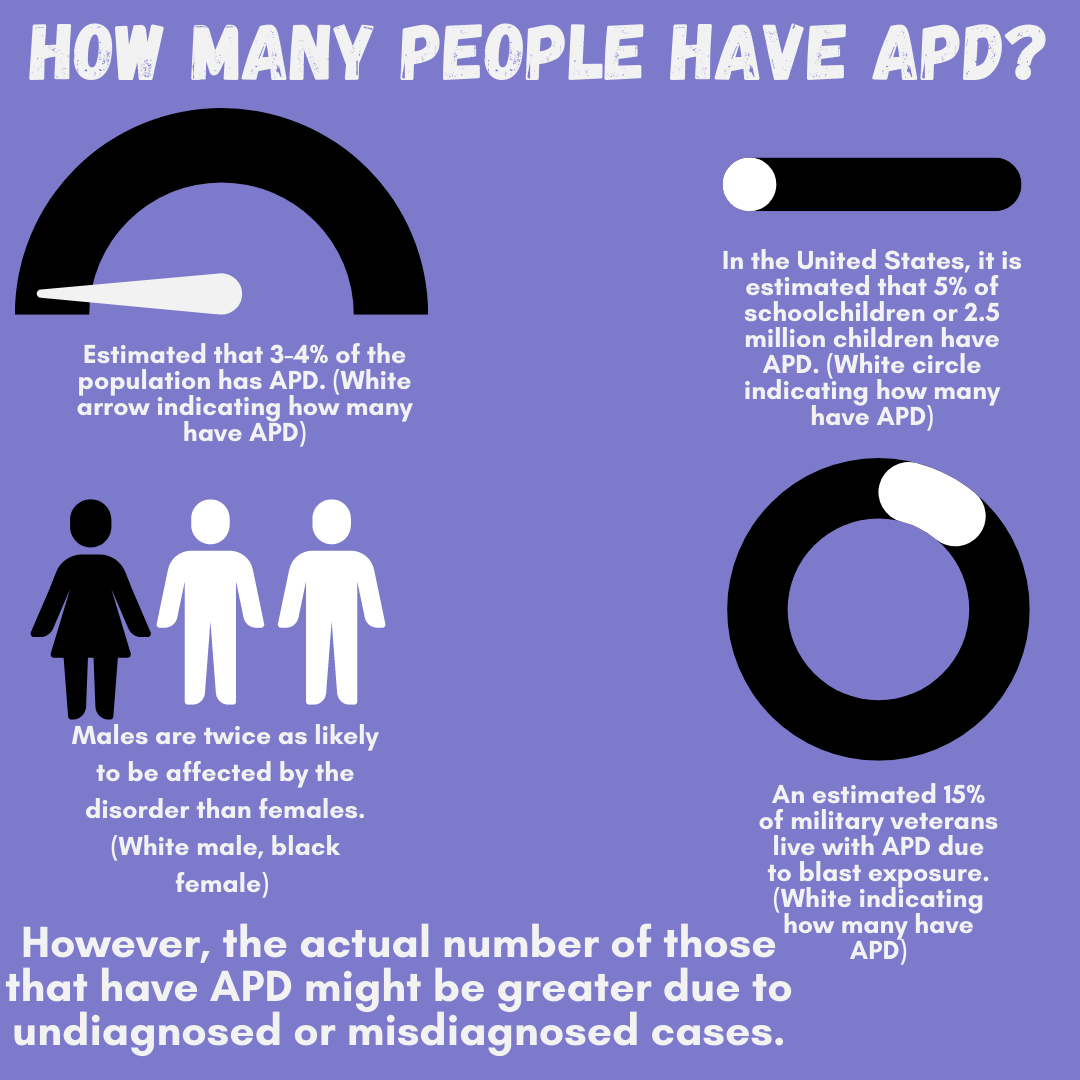

So let me invite you into the lives of the 3-5% who have this condition and what it entails, from diagnosis to living with the difficulty.

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett outlining estimates of people with APD. Data from the Handbook of central auditory processing disorder, Kids Health, Hearing health Foundation & Churchill Centre & School.

“Over the years that I've been working with this, I feel like auditory processing disorder is where auditory skills get in the way of living a full life. It's not auditory skills like you're not listening hard enough or you're not trying hard enough, I realised that it has less to do with how much someone wants to engage, and how much their neurology prevents them from processing what they are hearing.”

What is auditory processing disorder?

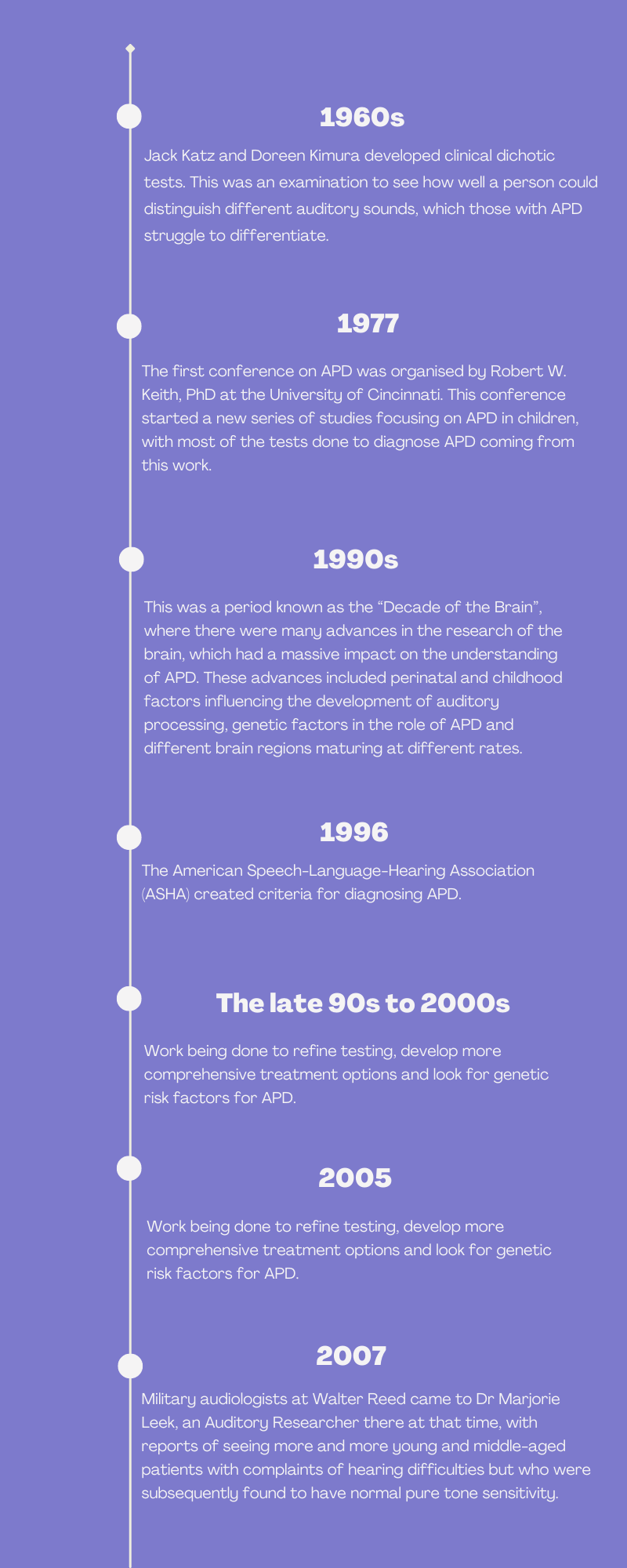

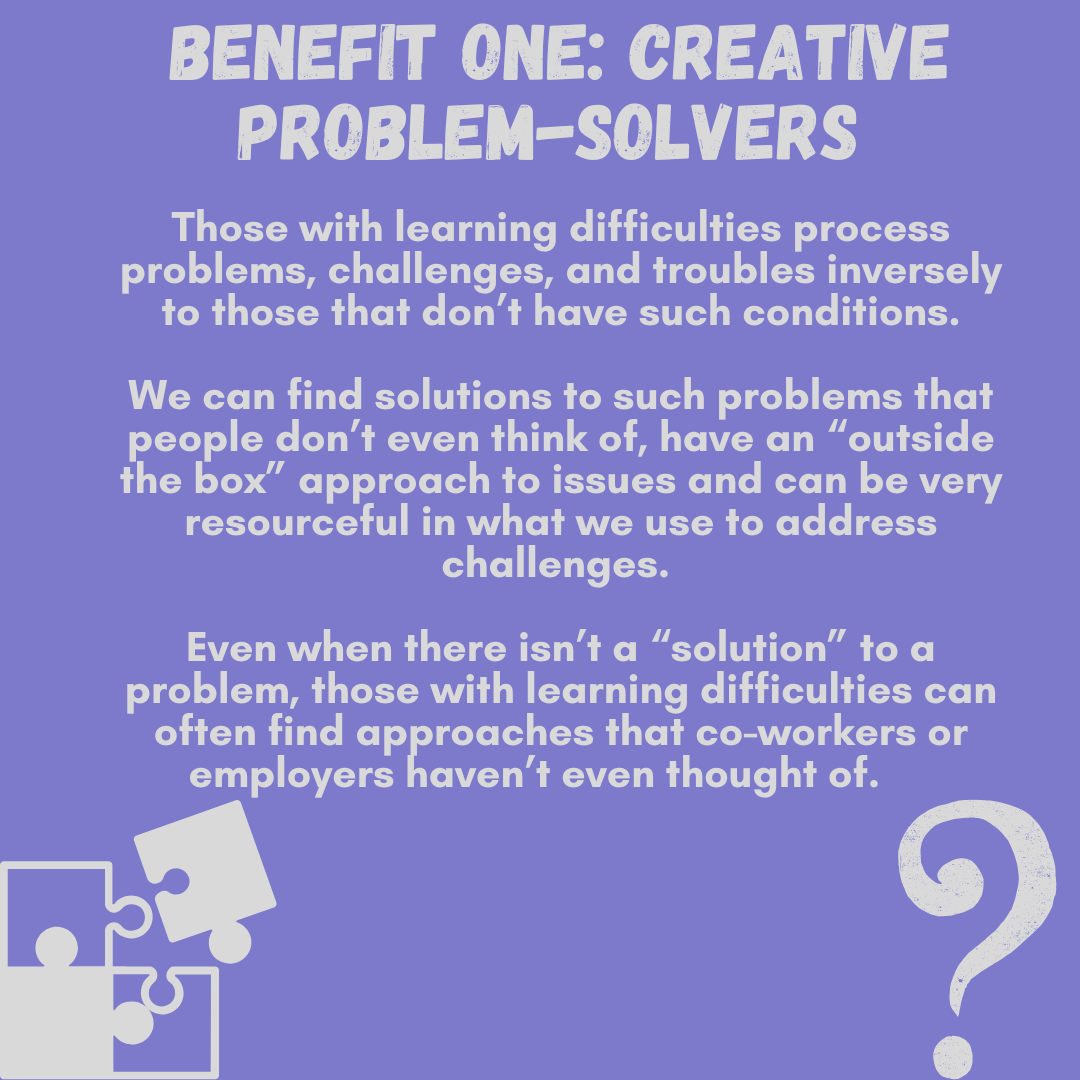

Despite not much information about the disability, there is a lot of historical context regarding APD. There are disagreements about when the term arrived, but from investigating the term's roots, 1926 is an important year. In 1926, Henry Head, a neurologist, first discovered the condition when he encountered soldiers fighting in World War One with head injuries that differed from aphasia. He distinguished between a deficit in auditory perception and a higher-order language processing disorder.

Twenty-two years later, Samuel J. Kopetzky also discovered the causes of APD. The condition was initially called King Kopetzky Syndrome (KKS), which refers to adults who seek help in the presence of normal audiometric thresholds. In 1954, Helmer Myklebust's "Auditory Disorders in Children" study found children with normal hearing yet unable to listen to unexpected sounds. Myklebust was seen as the “pioneer” in APD assessment.

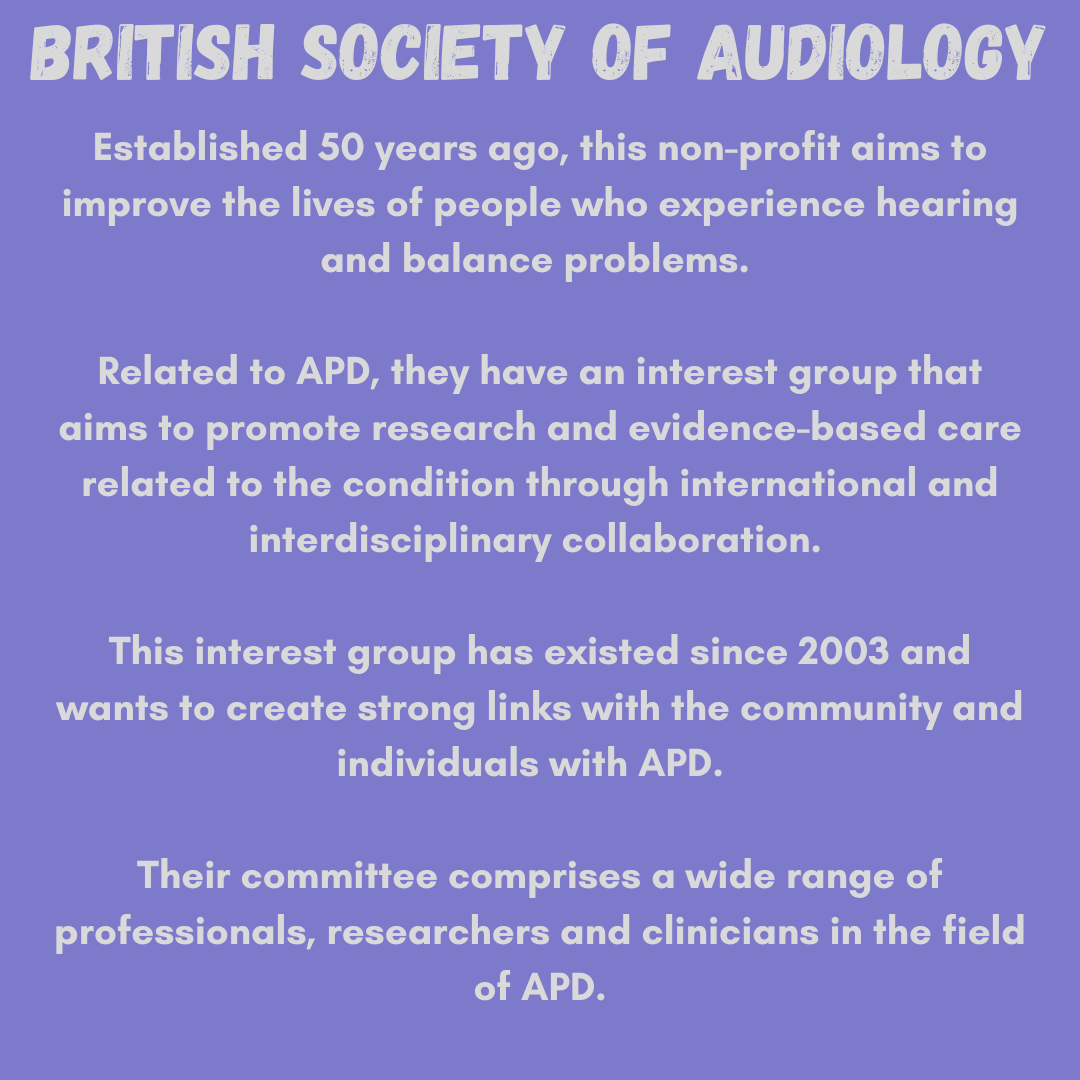

The ambiguity of when APD was first discovered continues in how it is defined. Cristina Murphy, an audiologist and researcher, explains this by indicating a lack of consensus regarding APD diagnosis, treatment, and the condition's nature. That is why multiple definitions appear when searching for a description of APD. The British Society of Audiology (BSA) defines APD as “an inability to perceive speech and non-speech sounds.” Compared to The National Health Service (NHS) they go as far as to say it is challenging to understand sounds such as spoken words.

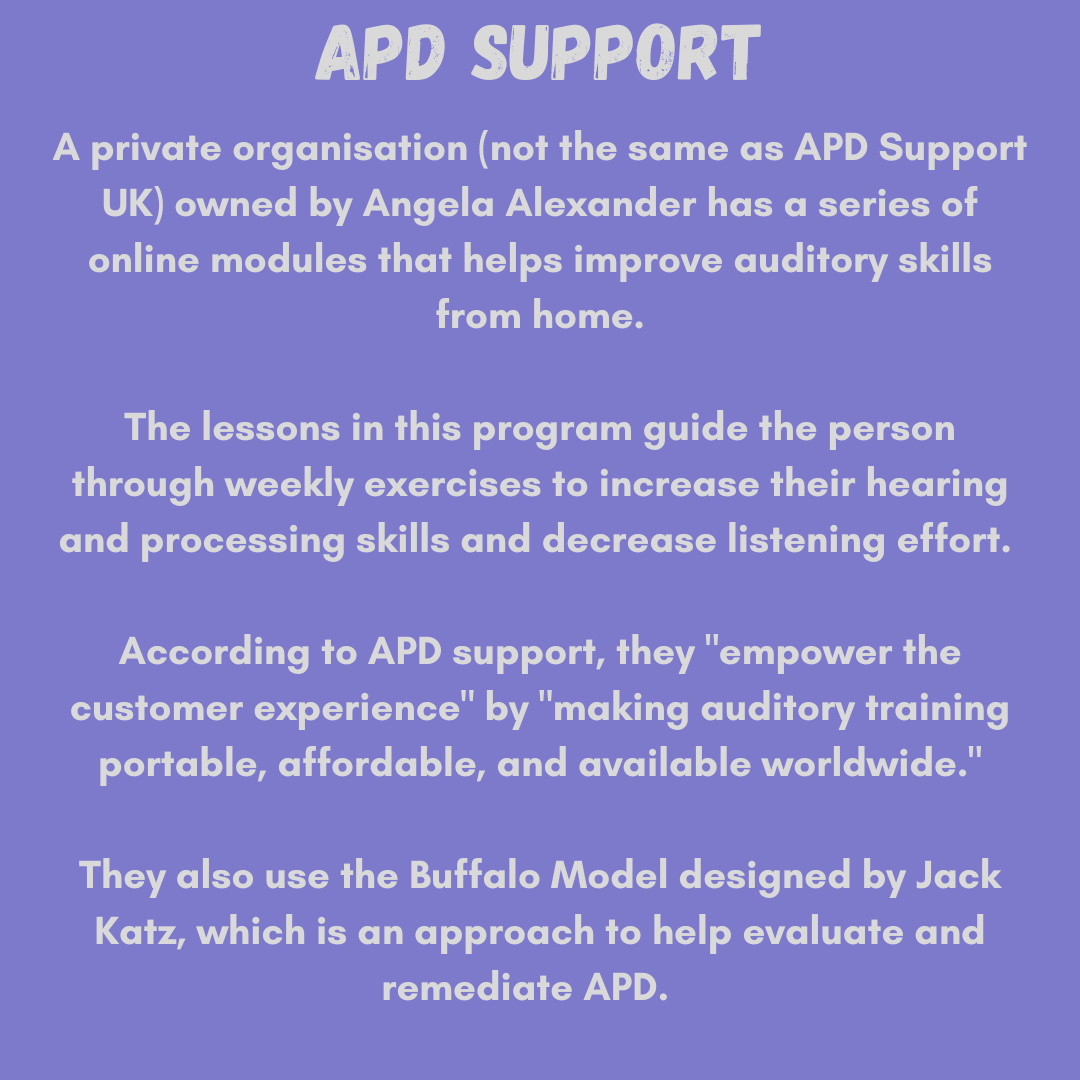

Speaking to Angela Alexander, an audiologist with a clinic called Hear Better Audiology in Taupo, New Zealand, she helped clarify what APD means. She said: “Auditory processing is what the brain does with what the ears hear, and an auditory processing disorder is when something goes wrong in that process.”

Hamish Hallett created a timeline about the history of APD. Information collected from Controversies in Central Auditory Processing Disorder by James Jerger, Audiology Online, Noise & Health Bimonthly Inter-Disciplinary Journal, Central auditory dysfunction: University of Cincinnati Medical Center Division of Audiology & Speech Pathology symposium, Thieme Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, American-Speech-Language-Association, British Legion, Veteran Affairs Center & The British Society of Audiology.

Symptoms of APD

There is a variance from person to person who has APD regarding their symptoms.

These symptoms include:

- difficulty listening to people speaking in noisy places

- trickiness with people with strong accents or fast talkers

- trouble distinguishing similar sounding words

- finding it challenging to follow spoken instructions

- annoyance in listening and watching videos that have multiple visual cues

Those with APD do not just have struggles with listening and understanding auditory speech. They also have communication challenges. These can include talking louder or softer than necessary and forgetting what to say during conversations. Some of the symptoms of APD were mentioned during the conversations that I had with those who have the condition.

Participant S, who is from Indiana and, for legal reasons, could not be named, finds it difficult to follow instructions.

“The hardest aspect of difficulty is being able to follow directions as I can't understand them, and I also experience seizures due to the brain injury.”

When speaking to Jacobs, his work as a therapist is sometimes affected by his condition.

“As a therapist, it requires listening and active listening. People often asked me a lot, like how can you do that? I think, for me, I had to retrain my brain essentially. I think one of the things that I have done a lot is if something doesn’t click or is a problem, I will ask a client to repeat what they said to me.”

KB has also struggled during conversations and often has to take breaks. They recalled a moment in a restaurant where they had to take some time out because their brain was overstimulated.

“I remember being in a loud restaurant where people were talking, dishes were smashed, and I was escaping to the bathroom and staying there for 10 to 15 minutes to catch my breath. My family knew what was going on with me, so they helped and took me to another table where it was quieter, and I could follow along with the conversation.”

Sarah Cortese, an owner/operator of Black Dahlia Tattoo Studio from South Jersey, had gone through similar experiences to others I interviewed. She specifically mentioned how she did a lot of “masking,” which means hiding aspects of her condition from others.

“I was doing the cycle of partying, drinking, and then just sleeping the day away, and now looking back, it makes a lot of sense. I think there were things I picked up in my 20s where I was overly social and overly socially drinking to get through how exhausting my brain and then my body felt. I didn't understand why my friends could have these conversations without struggling through it.”

Video interview clip of Sarah Cortese explaining to Hamish Hallett how her APD had affected her tattooing earlier in her career. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Despite clear symptoms of APD, there is a hidden symptom: the feeling of being misunderstood.

KB had to go to 15 different schools because schools and teachers didn't have the right accommodations for their APD. When asked about why people misunderstood their APD, they felt it was down to education.

“I feel like they automatically saw that auditory processing meant deaf or sometimes they thought that I was ignoring them when I just couldn't hear what they were saying…. I think it's just a lack of education because there's not that much information about auditory processing."

Cortese took a different angle when asked if she was misunderstood.

“I would say it was more of a dismissive reaction because you just accepted these behaviours and clumped them into one box and if you didn't fit into this box, that means that at the time, you just weren't a well-behaved kid.”

Jacobs not only felt misunderstood, but he hid his condition from others. It went to the extent of being involved in gang-related activities due to such a lack of understanding from others about his condition. Only after a death of a friend in a gang-related shooting was when Jacobs realised his feeling of being misunderstood was becoming serious.

“That was really the wake-up call for me and when things shifted. An eighth-grade teacher came into my life at the same time and she was very strict and stern. Yet, she steered me in the right direction and she was like the first teacher who saw something in me. It was the perfect storm at the right time.”

Video interview clip of Dr Sheldon A Jacobs explaining to Hamish Hallett about how he felt misunderstood. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Despite such drawbacks of having APD, there are some positives to having such a condition. With Jacobs, he mentioned his work ethic, self-advocacy and empathy as positives of having APD. Along similar lines, Cortese felt she has greater empathy for people, especially those who are neurodivergent. KB also mentioned advocacy and empathy as positives of her condition. They went a step further by suggesting that their APD has given them greater resilience.

“I have great resilience because of my APD. I Went to 15 different schools to try and find the right teacher for me and each teacher was judgmental and dismissed me. From that, I just needed to learn how to be strong.”

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett outlining common symptoms of APD. Information from National Health Service (NHS).

Video created by Hamish Hallett about when his brain is struggling to process information.

Video done by Hamish Hallett about when he forgets what to say or what word he wants to say.

Video done by Hamish Hallett struggling to explain what APD is.

Video created by Hamish Hallett explaining what having APD would be like versus what it's actually like.

Benefits of having a learning difficulty

Video created by Hamish Hallett outlining the strengths/benefits of having a learning difficulty

Infographics created by Hamish Hallett on the benefits/strengths of having a learning difficulty. Information from Noodle.

Drawbacks of having a learning difficulty

Video created by Hamish Hallett outlining the weakness/drawbacks of having a learning difficulty.

Infographics created by Hamish Hallett on the drawbacks of having a learning difficulty.

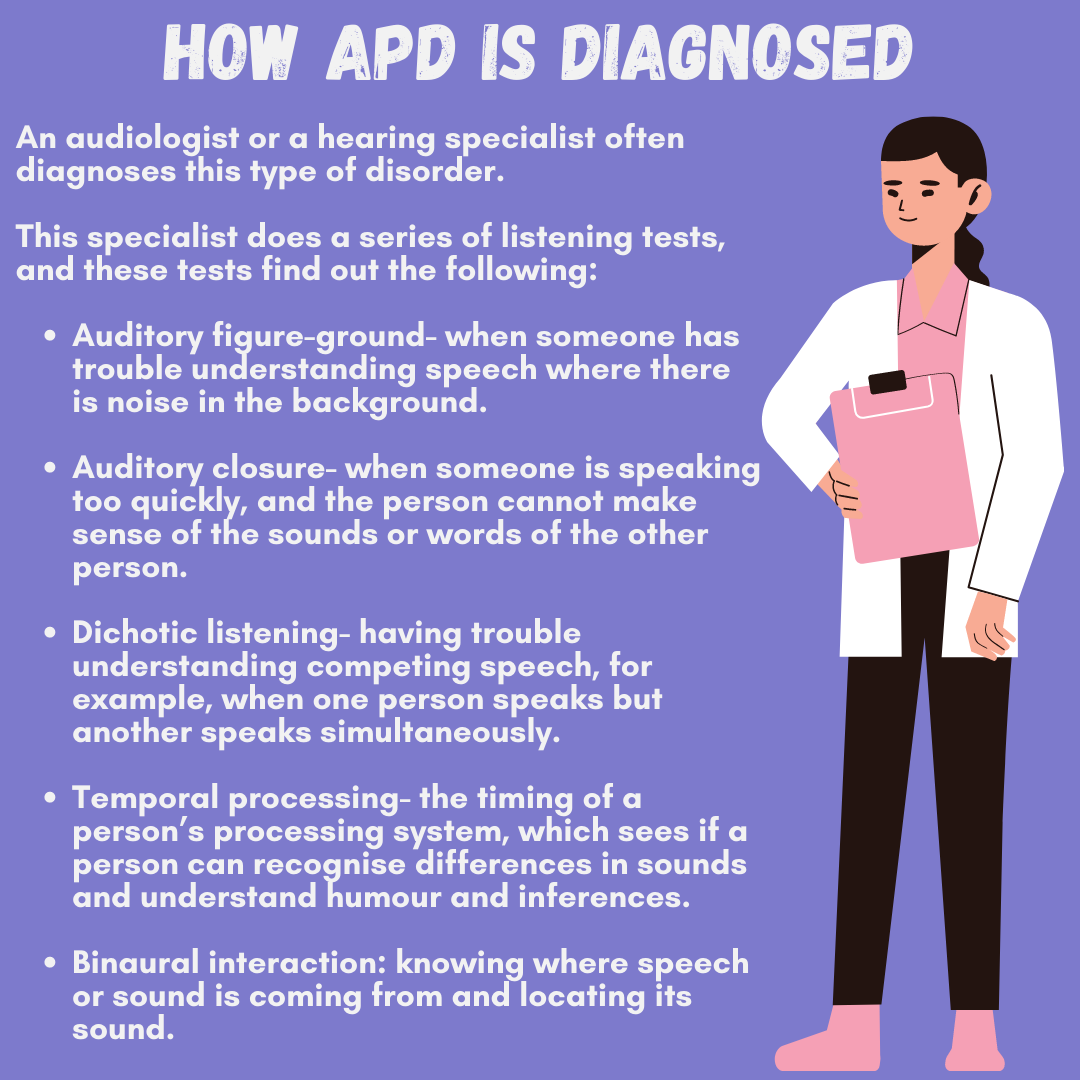

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett outlining how APD is diagnosed. Information from Kids Health.

Video of Sheldon A Jacobs spoke to Hamish Hallett about how he was diagnosed with APD. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Image of KB, who was diagnosed with APD after their mum noticed that they weren't speaking. Photo credit: KB.

Video interview of Sarah Cortese explaining to Hamish Hallett how she came to terms with her APD. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett on the military-related risk factors of developing APD. Information from Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research.

Video created by Hamish Hallett about the links between APD and the military.

How is APD diagnosed?

The most common way for APD to be diagnosed is by audiologists, who are hearing specialists. Usually, they create a selection of tests to determine what the person struggles with.

- The first test is where the audiologist looks at if the person has difficulty understanding speech when there is ambient noise in the background, called auditory figure-ground.

- The second test is finding out if the person finds it challenging hearing speech when the person is babbling or is muffled, which is called auditory closure.

- The third test is finding out if the person has difficulty hearing speech from two sets of people, which is called dichotic listening.

- The fourth test is to see if there is difficulty distinguishing speech sounds, called temporal processing.

- Lastly, the audiologist finds out if the person has difficulty locating sounds, called binaural interaction.

There seemed to be a sense of relief and clarity when diagnosed with the condition. Taking Jacob’s case, he felt a sense of clarity when he was diagnosed at the age of 11 years old.

“Before that point (before being diagnosed with APD), I was very behind in school, I was getting further and further behind, and so my school decided to get me tested to see if something was going on. I met with a school psychologist and did a bunch of different tests. Some weeks later, after doing all that testing, I was diagnosed with an auditory processing disorder. I knew I had a learning disability and learnt differently from most of my peers. Once I was diagnosed, it gave me more clarity, understanding, and awareness, and it changed many things for me.”

Along the same lines, KB had a similar experience to Jacob’s regarding how they were diagnosed.

“At the age of two, my mother saw something wrong with me, but she didn't know what it was. I wasn't speaking, and I just grew up having speech therapists. Several years later, I was diagnosed by an audiologist, where we did many hearing tests.”

However, not all diagnoses of APD are simple. Cortese said that her diagnosis of APD was rather complicated. Schools misunderstood her as being “jittery” and “easily distracted,” which led to her being forced to leave catholic school. Even though Cortese was diagnosed with APD during her younger years, only when she had her daughter did she start to gain clarity about her condition and how it affected her.

“For about 30 years, I just lived my life not understanding what this diagnosis meant until I had my daughter, who will be six in August. She was diagnosed at the age of 19 months, and I knew something was different. She was diagnosed on the autism spectrum, but I identified with her in so many ways I started getting involved in her therapies and doing a lot of parent training classes. As I talked to the therapist, they described the sensory processing disorder, particularly the auditory portion. I remember leaving and being in tears because I never felt that understood. Even though it was about my daughter, I never had somebody put it into words. It was life-changing for me, and I know parents always say this, but my daughter changed my life and opened many doors.”

Diagnosing people with APD happens when the participant is seven years old. However, how APD is acquired varies from person to person. The most common way APD is acquired is through genetics. Increasingly, there is more research coming out about military members acquiring APD. Melissa Papesh, a research investigator for the National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR), first encountered such links around 2007.

“Around this time, military audiologists at Walter Reed came to Dr Marjorie Leek, who was an Auditory Researcher there at that time, with reports of seeing more and more young and middle-aged patients with complaints of hearing difficulties but who were subsequently found to have normal pure tone sensitivity. It seemed one of the unifying features at that time was an increase in the number of military service members exposed to high-intensity blast discharges, particularly due to improvised explosive devices.”

Later on, Papesh explained how improvements in protective gear meant fewer service members had died from heavy blasts caused by explosions. Yet, this left a “gap” in knowledge about the effects of blast exposure on an individual who survived a blast.

“Dr Leek obtained government funding to study the impact of blast exposure on central auditory functioning, later in collaboration with Dr Frederick Gallun at the VA’s National Center for Rehabilitative Research. The results of this initial examination, published in 2012, revealed that many service members who had been blast-exposed with the past year demonstrated varying components of APD.”

When asked how prevalent APD is in the military, Papesh felt that there wasn't a “conclusive answer” due to the need to research this topic further. There are more traumatic cases away from the military and genetics being passed on. S told their story about how they acquired their condition.

“I was diagnosed with APD at eight years old, just a few years after my traumatic brain injury, by a team of neurologists. The head injury was caused by my foster mum throwing me out of a 3rd story flat when I was three years old because I was crying too much. Later, in 3rd grade, my APD was diagnosed through weeks of Neuro tests and other tests. They still don't know if my APD was pre-existing or my traumatic head injury.”

Subtypes of APD

Video created by Hamish Hallett showing subtypes of APD.

Infographics created by Hamish Hallett showcasing the subtypes of APD. Information from Kids Health.

The auditory cortex and how it differs for those with APD

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about the auditory cortex and how it differs for those with APD. Information from Science Direct.

Strategies to manage APD

Despite the complexities of APD, there are strategies to manage this condition. Jillian Steen, the owner of Grace Speech Therapy Services in Minnesota, said she had encountered a broad spectrum of people with APD. Steen has provided a wide range of strategies to those with APD to help manage their condition from a speech therapist's perspective. There are many benefits to going to a speech therapist, especially if someone has a condition like APD. The benefits of speech therapy can include improving the articulation of speech, development of social skills, and cognitive development. According to Steen, going to a speech therapist can help provide a medical understanding of the brain rather than just an educational one.

“An educator can provide the educational stance on the understanding and the anatomical mechanics of the brain, but with a speech therapist or through speech therapy training, you're getting the medical side as well. Kids benefit from it, everybody's individualised, and everybody's different, but that medical understanding makes a huge difference.”

There are other ways to manage this condition. In KB’s case, they have an FM transmission device that has helped them understand more clearly a person when speaking to them in classrooms or busy places. Military members also have these FM systems and hearing aids to help with their APD. An example of such can be seen by the launch of the Veterans Hearing Fund (VHF) as a result of the Lost Voices report commissioned by the Royal British Legion.

The organisation received £10 million of LIBOR funding to set up VHF, which helps provide hearing aids for veterans with APD or a hearing loss equivalent. Since launching in 2015, VHF has issued over 2,400 grants. Papesh mentioned that the military is looking at other ways to prevent the acquirement of APD or other hearing loss issues.

“How helmet designs interact with blast waves has led to some important redesigns that reduce the culmination of energy passing through the skull and brain. As we learn more about other factors that impact auditory function, additional protocols will be implemented to help mitigate the possibility of Service members developing APD, such as protocols for managing exposure to jet fuel fumes.”

Cortese has also found ways to manage her APD, whether with her tattooing or other situations. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic forcing businesses to shut down and having a limited amount of people in places, this has helped Cortese’s APD. She explained how she could control the amount of input she received while working at her tattoo studio.

“I understood that my body felt different by having a controlled environment and limited people in that space. I was tattooing, and I was not physically exhausted just from being in this room, and I was not fighting against things that were around me.”

Video clip of Sarah Cortese explaining to Hamish Hallett how she was able to manage her APD during and after the pandemic as a tattoo artist. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Video interview clip invoking Jillian Steen, owner of Grace Speech Therapy Services, talking to Hamish Hallett about what she does to help those with APD from a speech therapist point of view. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett on the benefits of going to a speech therapist. Information gathered from Ainscough Associates.

Infographics created by Hamish Hallett about the Lost Voices Report. Information gathered from Cobseo.

Organisations/resources that help people with APD

Infographics created by Hamish Hallett outlining three organisations that help people with APD.

Video interview of Jillian Steen speaking to Hamish Hallett about the lack of access to an audiologist and speech therapists. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Video interview of Angela Alexander speaking to Hamish Hallett about her profession being scared to make an APD diagnosis. Later in the interview, she spoke about how it was medical gaslighting to not diagnose someone with APD if there are clear symptoms of the condition. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

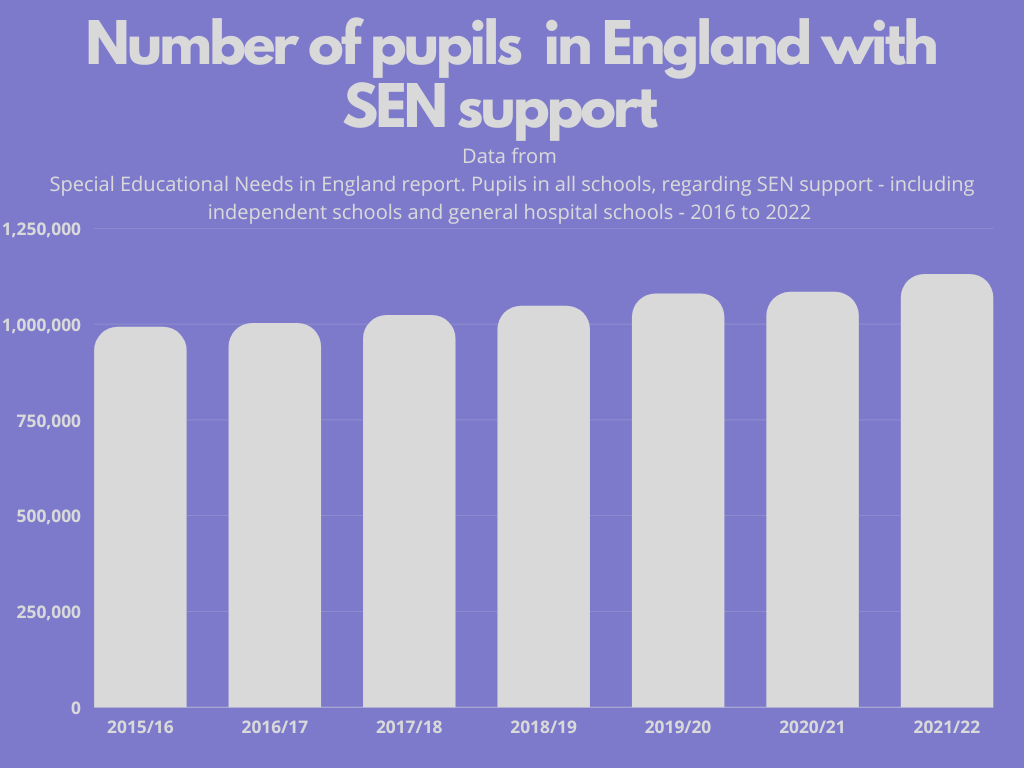

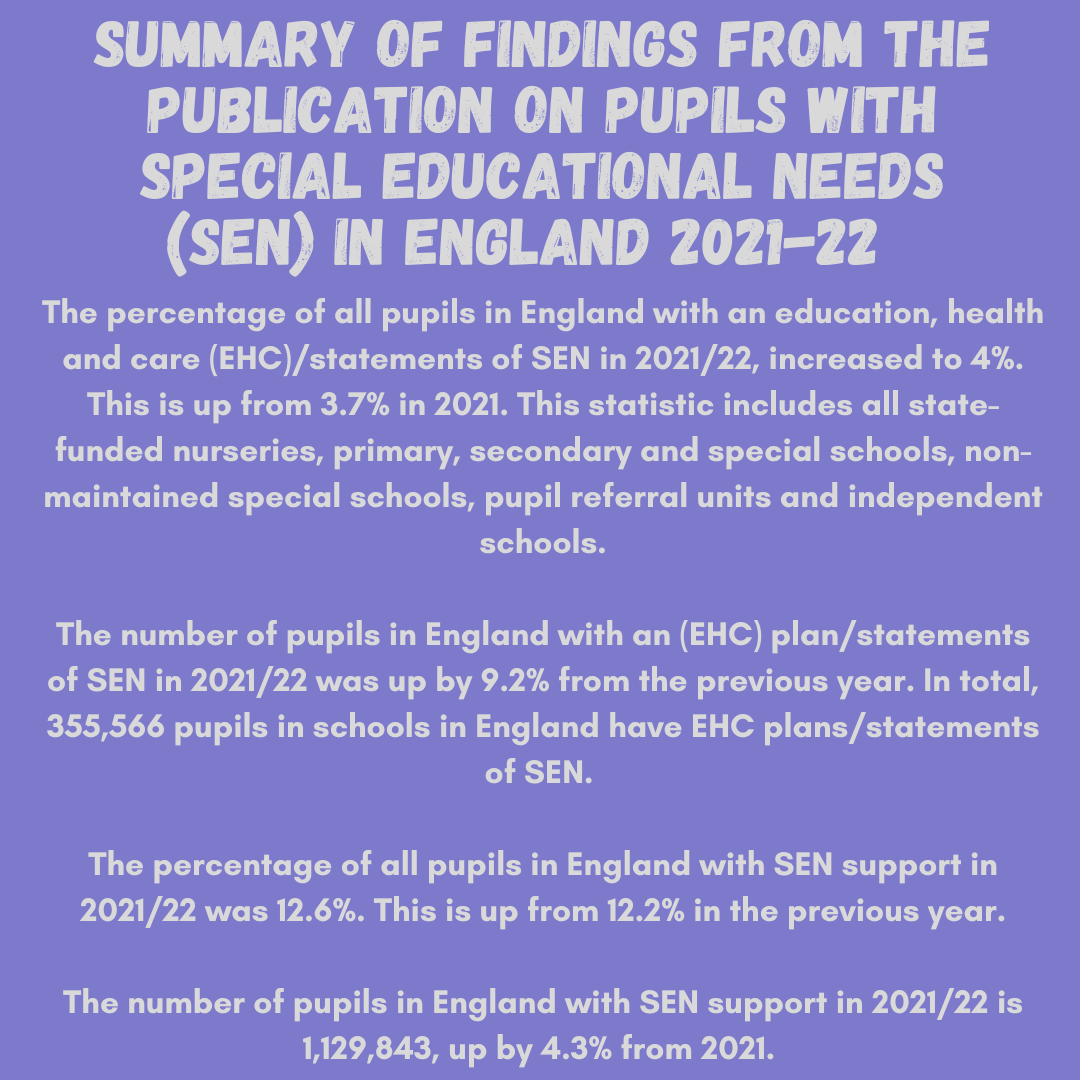

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about the number of pupils with SEN support in England increasing year by year. Data from Special Education Needs in England report.

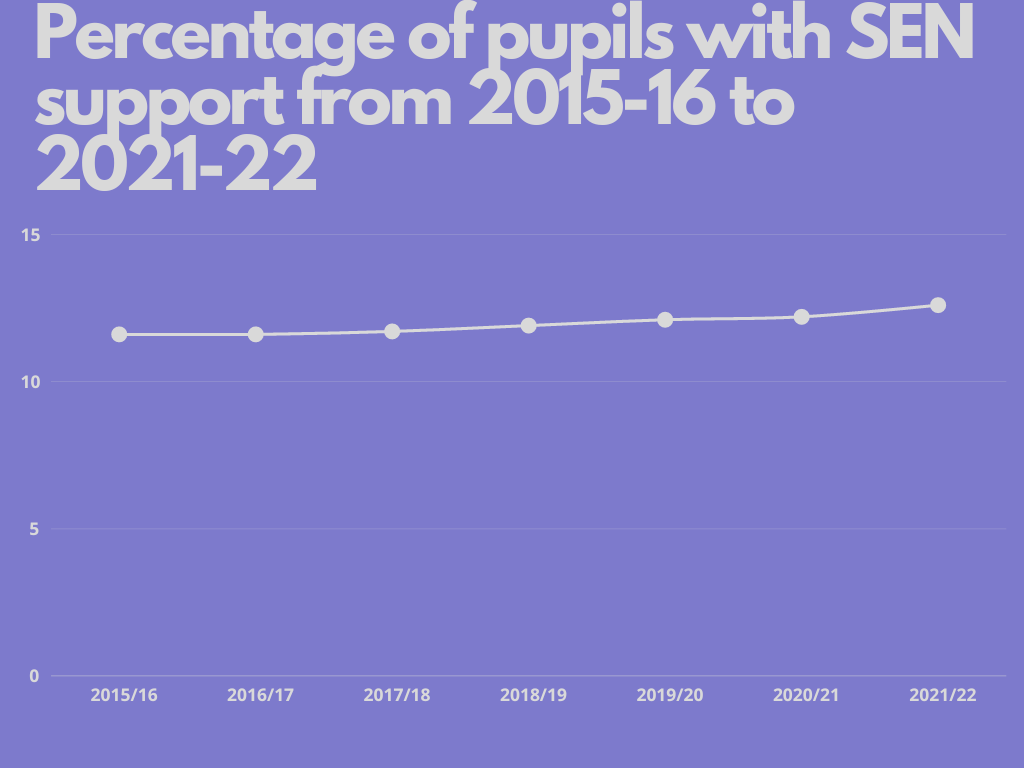

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about the number of pupils with SEN support in England increasing year by year by percentage. Data from Special Education Needs in England report.

Video interview of Jillian Steen speaking to Hamish Hallett about schools not understanding students with APD. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Video interview of Angela Alexander speaking to Hamish Hallett about schools not prepared to deal with students who have APD. Captions are available by clicking "subtitles/closed captions."

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about how teachers are confident in teaching students with additional needs.

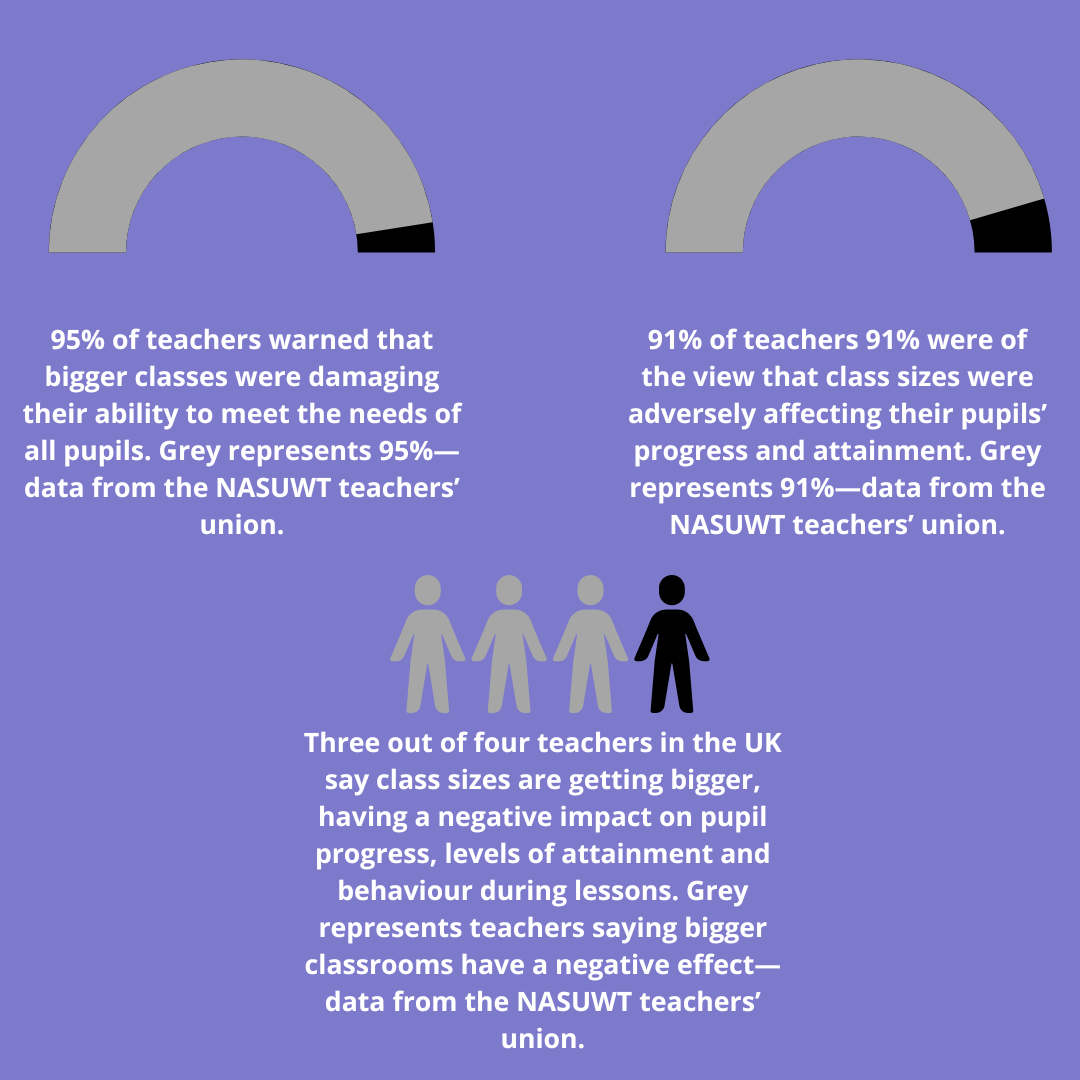

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about oversized classrooms in the United Kingdom.

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett summarising the findings from the publication on pupils with Special Education Needs (SEN) in England 2021-22.

The controversies surrounding APD

Even though there are strategies to help those with APD, there have been issues in gaining access to these strategies. Steen highlighted this, especially within her field of speech therapy as well as audiologists. She specifically mentioned the lack of these professionals across the United States.

“People fly to different states to have a diagnosis of APD for themselves or someone else. Only three audiologists in Minnesota do it, and parents will do whatever it takes for their children to be diagnosed. I had times when families would say we will pay for your Floria licence if you can help provide speech therapy services… I had a family willing to drive three and a half hours once a week to see me, and it is like these parents will do anything.”

When asked why there was a lack of such professionals, Steen felt that there was a lack of speech therapists trained in APD. When questioned about the audiology side, she felt that audiologists see APD as a “controversial disorder” and that it doesn't exist.

“They say because you can't change someone's processing time, it's not a real disorder, even though you can teach people strategies to help with someone’s processing. Much of this stems from Ignorance or the lack of personal exposure to APD, which is why some audiologists do not see it as a real disorder.”

Steen isn't the only one who suggests that people see APD as a controversial disorder. Alexander mentioned how audiologists are “afraid” of diagnosing the condition in her field of audiology.

“I am aware that my profession, in general, is afraid of the diagnosis of auditory processing because they don't know what to do with it. My profession is so used to black and white decisions on everything, and we are a very quantitative profession. We need to know very clearly where things are, and in the auditory system, we can often pinpoint exactly where an issue is happening. With auditory processing, we won't often know exactly where the issue is happening.”

Papesh also said that APD is seen to be controversial regarding why there was a lack of information about the military and the links with the condition. She mentioned that the frameworks set by associations related to this field, like the American Speech-Language, Hearing Association and the American Academy of Audiology, can restrict those having an APD diagnosis.

“ Even within well-connected healthcare systems such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, making such determinations is incredibly difficult. It was striking that relatively few audiologists used the ICD-10 code specific to Auditory Processing Disorder. Rather they tended to use more obscure diagnoses such as “Hearing Loss – unspecified” or “Abnormal Auditory Perception”.

Aside from speech therapists, audiologists and researchers, there are some barriers within schools regarding APD. Steen described speaking to schools about APD as a “different language” to them.

“They're teachers that would be exceptional for kids that go above and beyond with learning, but when they have accommodations, you're just speaking a different language to them. Barriers like that can determine what strategies are effective."

Alexander also described schools' lack of understanding about APD and suggested that schools are “unprepared” to deal with this condition.

Yet, despite it being seen and projected that schools aren’t capable of managing learning difficulties, there are question marks around if schools are being supported. In Australia, it was found that only 38% of teachers feel equipped to teach students with a learning disability. According to another survey conducted on California, Ohio, and North Carolina teachers, only 30% feel “strongly” that they can successfully teach students with learning disabilities. In the same study, only 50% believe those students can reach grade-level standards.

A lot of this lack of confidence regarding teachers supporting students with learning difficulties is due to a lack of teacher courses on how best to help those with learning difficulties. A study in 2007 found that “general-education teachers in a teacher-preparation program reported taking an average of 1.5 courses focusing on inclusion or special education, compared to about 11 courses for special-education teachers.” Another study this time in 2009 found similar results in that it concluded that teachers weren't shown how to teach to “different needs.”

What adds to the issue of helping students with APD are oversized classrooms. Across England, 494,675 pupils in primary schools were taught in classes of 31 or more in January 2022, up 2.6% from the previous year. There were also 438,101 secondary school pupils in classes of 31 or more, up from 4.7% the last year.

“The pupil: teacher ratio has risen again. This inevitably puts a squeeze on the individual attention of pupils. It is also further evidence that school funding is too low and some schools have to teach their pupils in unacceptably large classes."

There are 9 million school pupils in England from January 2022, with 16.5% or 1.49 million reported having additional educational needs. Out of 1.49 million, 1.13 million are on special education support (SEN), up by around 47,000 since January 2021. With classrooms being oversized, more students being diagnosed with learning difficulties, and teachers not feeling like they can support kids with additional needs, it could be why there is such a lack of understanding of students having APD.

Responding to such concerns, a United Kingdom government spokesperson said this:

“All disabled people, including those with Auditory Processing Disorder, deserve the same opportunities to thrive and reach their full potential as everyone else... All children and young people should receive the support they need to succeed in their education. To support this, we have raised funding for children and young people with complex needs in the next financial year 2022-23 by £1 billion to over £9.1 billion. This unprecedented increase of 13% comes on top of the £1.5 billion increase over the last two years and will continue to support local authorities and schools with the increasing costs they face.

Advice and help

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about helping kids with APD. Information is taken from Child Mind Institute.

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about the do's and the don'ts with people with APD. Information is taken from the NHS.

Infographic created by Hamish Hallett about how to improve auditory skills. Information is taken from the Pride Reading Program.

APD and beyond

From diagnosing to everyday life, there are many complexities, nuances and issues that arise from APD. It is a difficulty that though has information about it is still facing controversy from some sections of society. If that is from audiologists, schools and even people, there seems to be a long way to go for this condition to be fully accepted. It raises questions about what can be done to address such controversies if that is within the field of audiology, school or even society.

Talking to experts, researchers and people with the condition, it seems that the root of such controversy is around education. If that is from audiologists not knowing how to diagnose someone with the condition, teachers not feeling comfortable teaching students with different needs or people with APD not knowing how to manage their condition, the lack of education is the needle that threads through these problems.

What this article can try and do is create the education that is needed to address such an issue. It is a blueprint to illustrate the fundamental issues, problems and challenges that an APD diagnosis can bring. Showcasing the lived experiences of Jacobs, Cortese, and KB can demonstrate how APD has affected people and what can be done about it by those with or without the condition. The hope is to question how to prevent those with this condition to not go through such challenges.

These obstacles include going into gang-related activity, masking their condition or going to 15 different schools due to the lack of understanding of the condition. Speaking to experts that portray the lack of education or accessibility around this condition can start a conversation about how best to address this. Highlighting the challenges of schools and even the government can hopefully get to the root of why such issues and problems occur relating to APD. If that is through better teaching programs, higher investment or better techniques to diagnose people with APD, these are some of the solutions being discussed.

Where this article would like to end is on a note of optimism: what would you say to someone who was just diagnosed with APD?

There was a wide range of responses, all of which were uniquely given.

“It can be frustrating to mishear stuff, yet try to find tools to communicate effectively and not be afraid to speak up and advocate for yourself.”

“Number one, you have to learn about yourself. You have to understand what makes you authentic, what makes you tick, and what makes your brain work in the beautiful, magical way it does. Even though your brain is different, it is absolutely beautiful. You have to get down to understanding, knowing and being very authentic about that. Once you understand, advocate for yourself, but you can't advocate for yourself until you learn about who you are and how that affects the world around you.”

“Be proud of it. It's nothing wrong with you; you can learn uniquely, and I encourage you to embrace it as a positive.”

“I always say it's going to be okay. They've gone through every doctor, every testing, and it's just constant pointing, oh, go to this person or go to that person, and so when they do come to me, it's like, I can help. I am typically the first person to say I can help with battle upon battle.”

“Auditory processing is a great diagnosis because it helps us know how to move forward.”

Where will this subject go next is up to debate.

The hope is that this article can take this subject forward rather than backwards.