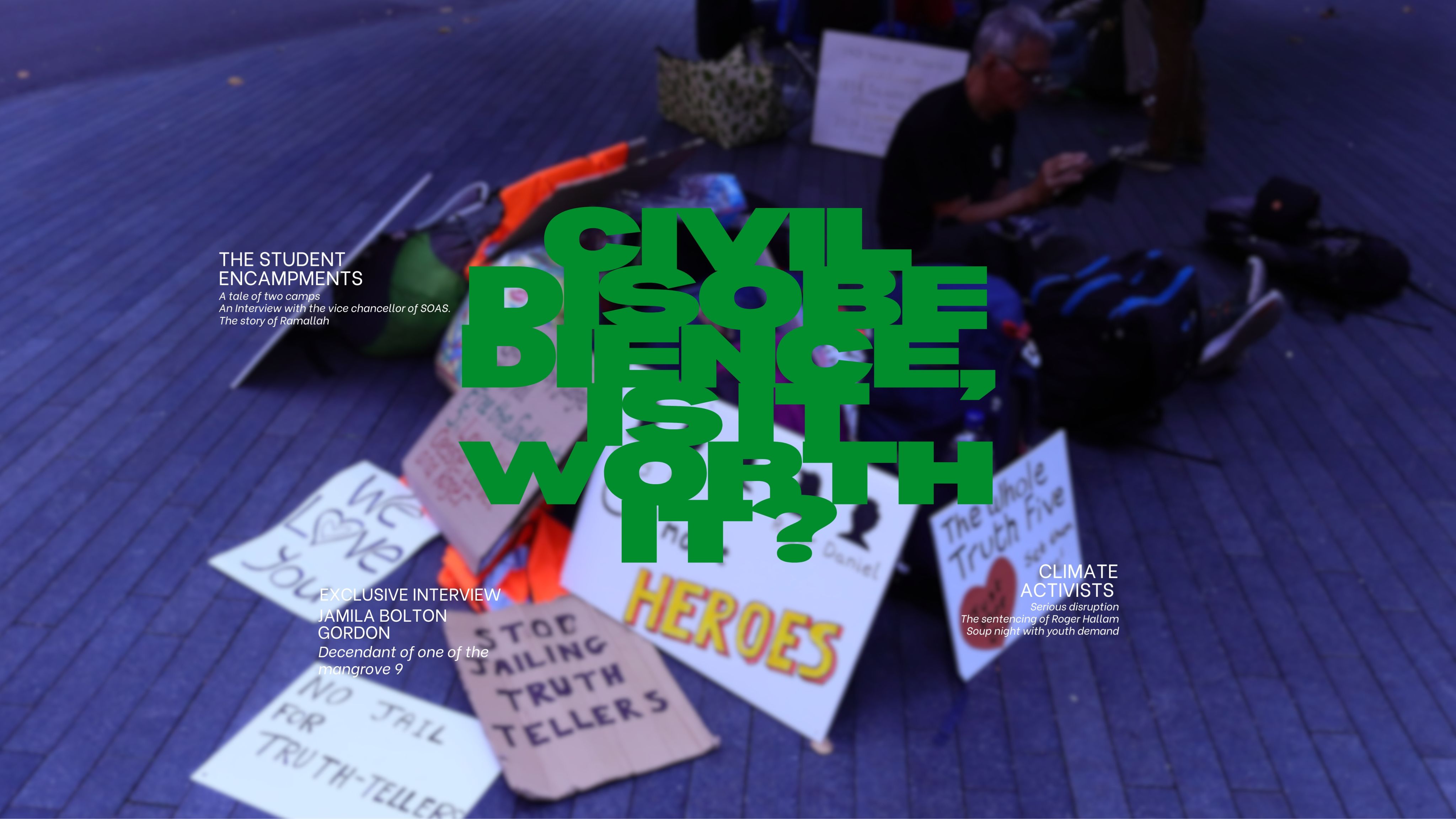

It is hard to predict where today’s rabble-rousers are headed. What is the verdict on protest movements like Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion or the pro-Palestine Student Encampments?.. This project is a deep dive into the methods of direct action they employ and why they think it's effective - or not. This project is the result of two months of close contact with campaign groups; Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, Youth Demand - and student activists from Cambridge, SOAS and UCL. The project includes Interviews and quotes from faculty members, academics and legal personnel.

The intention is not to advocate or criticise the moral standing of any individual or group featured in this project. Instead, it's a classic fly-on-the-wall attempt at exploring the seemingly taboo subject of civil disobedience, the individuals so passionately involved and the laws that work to keep it civil.

Context

When asked about the utility of an encampment protest, Dr David said;

" ..before the encampments, we saw a series of one or two-hour demonstrations - now it's moved to a permanent protest. This partly the aim of an encampment, establish a degree of permanence and create a sense that the issue isn't going away."

Bailey's work on political protests in Britain contains a detailed record of demonstrations from I985 to 2019. This record spans three decades of protests in the UK - collected from national newspapers. Of the over 2500 demonstrations logged in his book - 908 strayed from the more peaceful form of protest to the more confrontational. Meaning, over %60 of the protests during that period were non-confrontational. Compared to the other %30 which involved some blockade, trespassing, occupation, property damage, e-campaign (for example, hacking Website), non-harmful attack, violent attack, riot, or hunger strike. I asked Dr Bailey if the more confrontational ones turned out to be more effective overall. He said; “ It depends on the issue and what the government's perspective is at the time. For example, with anti-austerity protests - I found that some form of disruption was necessary, otherwise the government didn't seem to listen. However, with environmental protests, what mattered more was the willingness to continue protesting over time, so the length of the protest movement mattered more. But in virtually all cases where you have a confrontational movement, you also have the non-confrontational ones alongside which count towards cause..” Earlier this summer, students from nearly every major campus in the UK began to put up tents around their campuses as a method of protest. Although, camping overnight on uni ground does not seem immediately confrontational - the camps have taken up a life of their own as per the reason they were set up in the first place, which is in protest.

The University of Cambridge, Kings College.

“ For me, the most exciting thing about this form of protest is how we have changed the shape of the city and broken down barriers between town and gown. We are building a community of support which hasn’t existed in Cambridge before - at least not in my memory.” Monk. Former Cambridge Student. Member of Cambridge Encampment for Palestine. University of Cambridge.

Speaking with Monk, for him the camp not only represents an attempt at pressuring their university to cut all financial ties with the current Israeli government and to support a cease-fire - but also with its makeshift garden, and floating banners with faded messages of government resistance - the camp also represents as a sort of democratic reimagining of the public space, he's known as a student. The barrier of “town and gown - or town versus gown” that Monk mentions is a distinction between the Cambridge locals and the University of Cambridge as an institution - and in his memory never have the the two halves - town and gown - been so related in one shared space.

“ We have chosen a method that is sustainable and allows for long-term engagement - which isn't required for civil disobedience as a definition, but it is an element that we've adopted and carried in ”

JJ, Postgraduate Student. Member of Cambridge Encampment for Palestine. University of Cambridge. Sustainable civil disobedience sounds like a contradiction. How can one thing be both disruptive and sustainable at the same time? But as far as the community set-up goes, the Cambridge camp seems very self-sufficient, and yes, sustainable. They have community guidelines, a waste management team, a catering team, camp stewards and a group of student representatives all of who meet regularly with the university, in the name of negotiations.

Statement from Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Education. University of Cambridge;

“ We were glad to meet our students as we have been willing to do from the first day of the protest. While we understand some will see it as a negotiation, we see it as a constructive dialogue. In response to, concerns from the wider community - our priority is the safety of all our students and staff, and we have regular contact with our Jewish students and chaplains, assuring them of our support and that we will not tolerate antisemitism.”

On May 6th 2024, the Cambridge encampment for Palestine set its tents on the Kings College lawn in Central Cambridge. Within the first 8 days, they let out an offer for negotiations with the University. On May 15th, after the university failed to meet the deadline, some students moved and set a second encampment on the Senate Lawn. Due to this escalation, on May 16th, the university agreed to open negotiations - after which the group on the senate lawn returned to the main encampment.

In addition to opening negotiations, the University also agreed to certain preconditions. For example, none of the students from the camp would be subject to expulsion or any disciplinary action by the university.

“ We signed open letters, we protested, we spoke with senior staff, we met with our tutors, we tried the SU route - if you have tried every single available channel that is the proper way of doing things and none of it works, naturally, it would lead to a greater escalation and that's where the idea for an encampment came from. ” Bassil, Undergraduate. Member of Cambridge Encampment for Palestine. University of Cambridge.

A couple of weeks had passed and there had been yet another escalation. A group of students sprayed the senate building with red paint. But It was a different group. The encampment had effectively separated itself from the actions of those individuals, In the hopes that it would keep on negotiating with the university. As of this moment, [July 23rd, 2024] the University is yet to release any new commitment towards meeting the student demands - Although, most of its negotiations with the encampment have been confidential and out of the public domain. I emailed senior facility members at Cambridge for further comment but received no response.

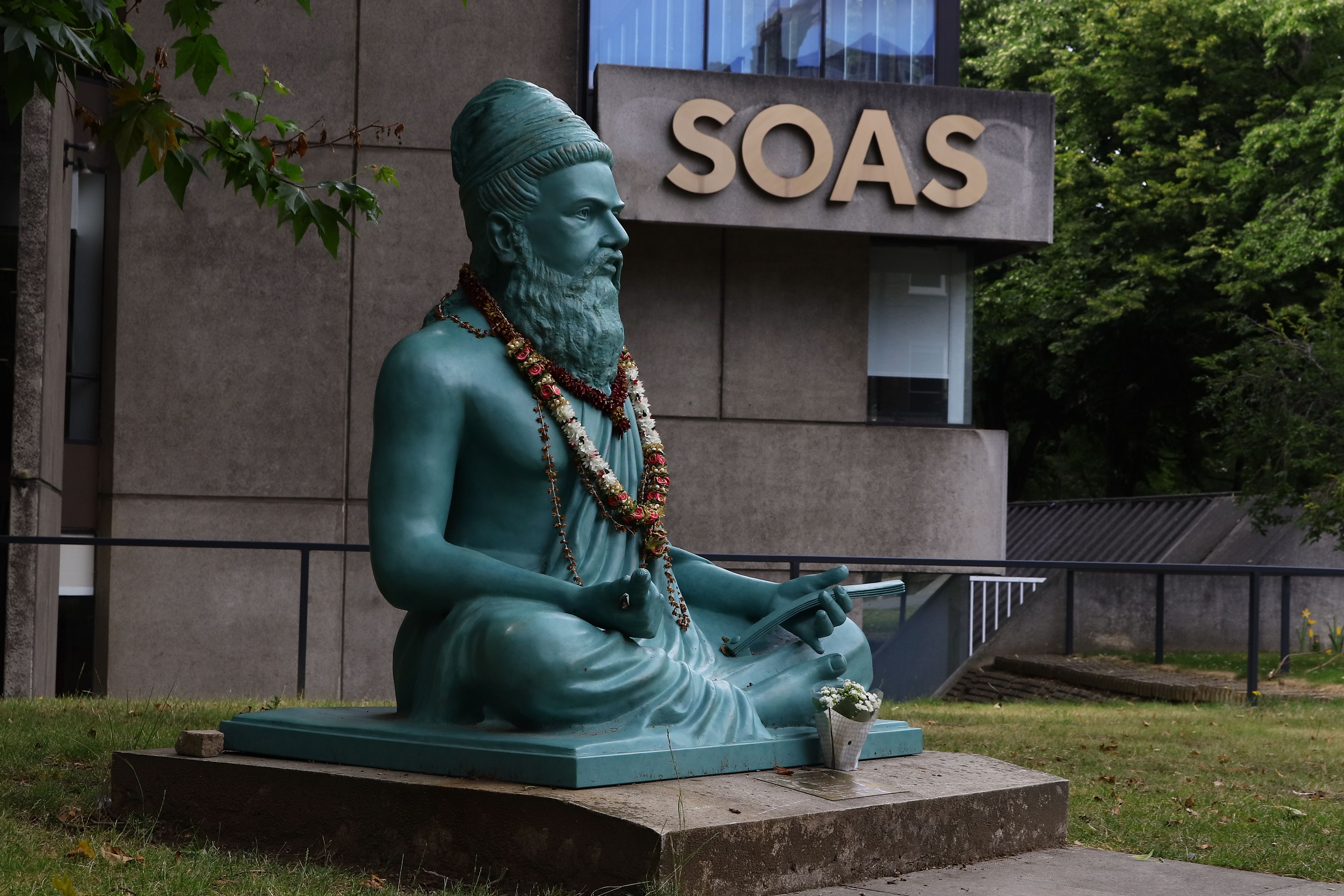

School of Oriental and African Studies, London

“ There are groups working with similar goals but with different methods and different networks. Different positionalities come into play when we are trying to create a social justice community. ”

Koru, Postgraduate. Member of SOAS Liberated Zone for Gaza. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. On July 12, the University of London approached the court for a possession order to remove the SOAS encampment. A possession order that is still pending. There had been recent escalations at SOAS too, but unlike the Cambridge encampment, the SOAS encampment did not separate itself from the actions of those individuals - and although some students were already facing expulsion by the university - the camp as a whole may soon face court action.

SOAS and Cambridge formed student camps on the same day. Before negotiation started - there was first the issue of location. The encampment wanted negotiations to take place outside, in the camp. Faculty thought this would be to be too much of an 'unneutral' ground.

Although they pitched their tents the same day as the Cambridge camp - the visible strain of the 50-day hold-out was more visible at the SOAS encampment. official name; SOAS Liberated Zone for Gaza. Altercations broke out between student members and security, the police were invited onto the premises once or twice, and a verbal confrontation between a student activist and the vice-chancellor was published online.

While Cambridge had its moment of escalation at the senate and ended up managing to force negotiations as a result - escalations at the SOAS camp seemed to yield a tougher response in comparison - which in turn, fanned more escalations.

But compared to Cambridge where the management had kept any ongoing negotiations with the camp out of the public domain - SOAS publicly disclosed its investments in March 2024 as per one of the student's demands.

The student demands are thus;

They say their university must disclose its list of financial investments, and if found to have financial ties with the current Israeli government, or more specifically, if found to have any investment or shares in arms companies contracted by the Israeli government, the university should remove those assets and sell off its investments outright.

They hope that their university withdrawing its funds, this put financial pressure on the Israeli government to support a cease-fire action in Gaza.

If the university agrees to disclose its investments and proceeds to divest from these companies, the third demand is that they reinvest the money into scholarships for students whose education was affected as a result of the war.

The fourth and final demand is for the university to protect those who currently live in the encampments.

And until these four demands are met, the students are willing to remain on campus grounds during exams and throughout the summer holidays.

..That balance is what the art of managing a public institution is about." Interview with the Vice Chancellor of SOAS University.

Can you please introduce yourself?

My name is Adam Habib. I am the Vice Chancellor of SOAS, University of London. I have been in this position for three and a half years. For eight years prior I was the Vice Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. I've been an Higher Education Executive for close to 18 years.

What are some differences and similarities between the two systems?

In South Africa, the universities at least get a portion of their finances through subsidies from the government, and fees are only a part of the financing arrangement. In the UK, especially since the cut in 2010, the universities, are solely dependent on fees. But problems around politics of free education, the debates around civil disobedience, what are legitimate behaviour parameters, those kinds of things cross national and continental divides.

On the 12th of July, SOAS sent out a press release saying, the University of London approached the court for a possession order to remove the SOAS encampment. How long has this discussion been going on, and why is a possession order being put in place?

Firstly, it is not a SOAS possession order, it will be a University of London possession order. And that's because SOAS only owns the buildings. It's a peculiar arrangement. We're one of the only universities where we own the building, but not the ground it's on. The reason for the possession order is a very simple one. When the encampment happened at SOAS, we said we would allow the encampment on four main conditions. One, don't engage in violence. Two, no hate speech. Three, don't target individuals in our community. And four, don't disrupt our exams or the usual operation of the university. In the first five weeks, they broadly abided by those rules. But In the last three weeks, they've violated them. They've tried to occupy the buildings and in one case, assaulted a security staff member. They've targeted individuals, myself included. And, so when the executive committee reflected on this three weeks ago, they decided to open a conversation with the University of London to close the encampment.

Some individuals are already facing suspension for some of the violations you’ve mentioned - does the whole camp have to face disciplinary action too?

Initially, our approach was that we would direct the violations at the individuals, and not at the whole camp. That's how we managed it up until three weeks ago. Now, we have a situation where we don't even know which ones are our students and which ones aren't. Seventy per cent of the camp are no longer students, there are people there who are homeless, and there are people there who are family members of students. There's a person there who's on a watch list. We can't ordinarily suspend them because they have no association with the university, except being there. We have no authority, and so in that context, we have to look at, the closure of the encampment.

In that same press release, it says; “we recall Martin Luther King's argument that protests, even peaceful protests, have to make people uncomfortable and be administratively and institutionally Inconvenient. this is the price of living in a democracy” - here the press article from SOAS does accept that a level of inconvenience comes with protests. What is the line they've crossed for you?

The argument between Martin Luther King and Stokely Carmichael is an argument that takes place in every liberation struggle around the world. It was an argument in South Africa. It was an argument in the Indian civil rights struggle. It is the argument in Palestine. It is the argument in Israel. And that is about the value of a peaceful protest, and what are the parameters. As Martin Luther King said, It should make you uncomfortable, It must cost us money, and it will be administratively inconvenient. For example, several people have written to me saying, they feel uncomfortable coming to campus. And I said, I acknowledge you're uncomfortable and you shouldn't feel uncomfortable, but that's the price we have to pay in a democracy, we recognize that it is a fundamental right in many ways. However, the real question is when do you cross the divide between being uncomfortable to violating. Well, when you violate the rights of others, when you become violent, when you engage in hate speech. When you break the law. And in that context, it becomes more than a simple inconvenience. It becomes, frankly, the violation of the rights of others.

How can the students of SOAS University best make their case?

Some individuals have been involved in the negotiations have said they want to participate. They've been courteous, and they've engaged with a view of the issues. They put their views forward and heard why some of those views could not be implemented and they've looked for compromise. For example, the first demand was to disclose our finances and our investments. We've agreed to that. They also wanted scholarships for Palestinian students in Gaza who can't study, and SOAS has agreed to a minimum of 7 new scholarships for Palestinian students. The thing that has become difficult is - they say we mustn't invest in armaments companies. We don't invest in armaments companies. We have an ethical investment policy that doesn't allow us to invest in military companies. They say, well, you must stop investing in companies like Amazon, Microsoft or Barclays - because of financial ties with the Israeli government. I can’t do that - because firstly, Amazon is not a military company. Secondly, our endowment is not free money - all of our endowment is attached to companies and if we don't get a good return, it means we can't give scholarships to poor students. And so there will be a direct consequence of that. By the way, we’ve divested from Barclays and sold all of the Barclays shares on the 14th of June. We do have a banking relationship in which Barclays gives us an overdraft facility. I can't get rid of an overdraft facility because that's what we use to pay salaries.

Earlier you mentioned the “accumulation of resources" that the UK universities have - can't the universities manage on this?

The problem is, that we can manage but not in a manner that is fair to every student in the UK. So think about this. If you're a poor person from Tower Hamlet coming to pay a fee, and if you're a rich kid from the richest place? let's say Chelsea, coming to the university. You come in, and both of you inherit a debt because that's paid for by a loan system. The student from Chelsea, their parents help to pay off the debt. Whereas the child from Tower Hamlet, their parent can't pay off the debt. That's where things like grant support and scholarships come in. Earlier, I was comparing our system to South Africa, but if you compare ours to Germany, which is more equivalent to the UK, in Germany, the state funds higher education - In the UK, the state doesn't. And so, when you say we can manage, we can manage compared to South Africa.

Have you, yourself, been involved in protests or direct action in the past? As a student maybe..?

I grew up in South Africa. I was an activist from the age of 15. I was immersed in the anti-apartheid struggle. I spent time in prison. I participated in and led movements, anti-war movements around the Iraq war. I was deported from the United States in 2006. I suspect, because I participated in the anti-war movement. I took the Obama regime to court, and eventually, they withdrew the case and settled out of court. And so, yes, I've been involved in civic protest all my life.

Would you say that part of your youth was well spent..? and seeing as you have this background, can you empathise with the students?

Both, uh, are yes. So firstly, I think it was important what I did. I grew up in a particular political milieu of a society that was racialized and segregated and you had to object to it and fight it. Despite all of the challenges of South Africa today, it is a far better place than the South Africa of 30, and 40 years ago. And that's something that would not have happened, without millions of people, mine being a very small contribution among millions. The second is I have an enormous sympathy for social struggles. And it is important to remember this. I want to read you a line from my book because it speaks to your question. I start this book on Rebels and Rage with the following words. We are haunted executives at the University. Haunted. Haunted by the fear that we will not rise to the strategic challenges of our era. We do not have the ideological comfort of those at the barricades where there is a certainty in their critique. But neither do we have the emotional serenity of the mainstream corporate executive who is comfortable with the world as it is. We occupy a lonely netherworld. Where we recognize that things can and yet must change, yet know that we have to operate within the financial and political constraints of the present. When I manage a university, I'm haunted, because I know that the world is not fair and that we need a better and fairer world. And I need to use my position to make it a better and fairer world. But at the same time, I have to operate within a framework that would allow the university to survive, getting the balance between paying the salaries I have to pay - and changing the world for the better. That balance is what the art of managing a public institution is about.

"It's sacrifice, it's liberation": The Story of Ramallah

“ I got the notice in the middle of a rally - my friends became scared for me, and it was just like damn!." JJ, Undergraduate. Member of UCL Stand for Justice. University College London. Ramallah, age 19 is a first-year student at University College London, studying social sciences. She is facing the possibility of two suspensions for allegations of obstruction and physical assault against security personnel. In one instance she and members of her encampment disrupted an awards ceremony at UCL - in a bid to escalate their demands. The demonstration resulted in security removing the students, and the assault allegation Ramallah says, was in self-defence after a security guard tried to 'grab' her. She says, “It was bound to happen in a situation with such high tensions”. On the 26th of June, Ramallah had her disciplinary interview via Teams. “It was just me and a UCL case worker. She just kept on reading the allegations, and every time I tried to relate back to our activism, the case worker just wasn't interested at all, the whole vibe from her was very emotionless.”

Ramallah’s full disciplinary hearing is set for the end of July, where she meets with the board members. "The middle of August is where I would find out what's going on”. She laughs nervously. Asking Ramallah if facing expulsion was worth it to her - She said, “If I am to lose my place at UCL I can go and apply somewhere else - but the Palestinian student that loses their place because their universities are now rubble, have nowhere else - there is an acknowledgement of the privilege we have, so this isn't sacrifice, its liberation.

Context

Dr Ruth's research is in the area of environmental crime and harm, with a particular focus on climate change countermovements.

“..Climate change is such a global issue, i don't think single direct actions or civil disobedience is a sustainable way to gain support for the cause. Climate action needs to me localised and long term - groups like just stop oil would be more effective if they worked at the community level to engage more people and to organise.”

Her book called "The Climate Change Counter Movement: How the Fossil Fuel Industry Sought to Delay Climate Action” - chronicles the emergence of a global counter-movement against climate change between 1980 and the early 2000s. In my interview with Dr Ruth, she mentions the role that climate obstruction plays in making climate action more difficult. Climate Obstruction are actions taken by certain groups to stop us from making progress on climate change. "It includes the actions of corporations, media organisations, research institutes and think tanks.” Climate obstruction can be the result of years of dependency on fossil fuels followed by a general reluctance by industries to adapt their business model to more renewable options. It becomes more of a purposeful obstruction when new government policies and actions begin to build on this reluctance. For example, the Rosebank Field development project is meant to reduce the UK’s dependence on imported energy by increasing domestic energy production. However, the method being used by groups - Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion - to combat this obstruction has come under a tightening response by the government and its law enforcement. In a Freedom of Information Act from the Metropolitan Police it showed between 2019 and 2022 - over 4000 protesters from the group Extinction Rebellion, were arrested at demonstrations around the country, followed by 1000 and more protesters from Just Stop Oil. Their demands in broad terms are - for the UK government to put an end to new fossil fuel licencing and production in the UK, for a systematic transition to renewable energy, and for the construction of citizen's assembly to guide the transition towards a fossil-free future. And for these demands, they will employ some peaceful protests and some disruptive ones, in a bid to escalate their demands. Some popular methods include; road blockades, slow matches, mass-sit-ins, chaining oneself to a gate, and pouring soup on public art which amounts to damage to property. More recently, [June 28th] over 20 Just Stop Oil organisers and members were arrested by police for conspiracy to disrupt national infrastructure. According to Dr Ruth; “Part of the climate obstruction we are witnessing today is with the new laws - the new public order act Public Order Act 2023 has slowly brought about the criminalisation of climate protesters”

Can protesters who feel their rights have been infringed on - bring a claim against the government?

Absolutely. So if you're organizing a protest and the police say that it can't take place then you absolutely can sue the police for Interfering with your right to protest.

But why don't most people just do that?

So, I mean it's very difficult because what usually happens is the police will tell you at the very last minute like, we're going to put these conditions on your protest. It can't go ahead for these reasons. So often it's very last minute, which makes it very difficult to do anything. I have been involved in a lot of cases where you're sending very last minute letters to the police saying, let this protest go ahead.

There's this phrase that keeps on coming up every time. It's the phrase “serious disruption” How would you define something that amounts to serious disruption, that would then need the police, to intervene?

There is a list of examples included in the act [The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022], which include things like a serious delay to essential goods and services or anything that amounts to the disruption to the life of the community - which could mean, closing down an area for a whole day. I think it is quite subjective. The important thing to know is that it does have to be serious.

Okay. So less on the word, disruption, and more on the word serious, what would amount to something serious? Does it have to involve some time of harm?

That is a question for the police - and it's going to be fact-specific on each case. I can't define what a seriously disruptive protest would be, but the law says, serious. I think it is to be interpreted by protesters and by the police.

Do you agree with the following statements from Judge Leonard Hoffman; “Civil disobedience has a long and honourable history in this country, people who break the law to affirm their belief in the injustice of a law or government action are sometimes vindicated by history. But there are conventions which are generally accepted; that the protesters behave with a sense of proportion and vouch for the sincerity of their beliefs by accepting the penalty, and that the prosecutor behaves with restraint to impose sentences which take the conscientious motives of the protesters into account.” First, do you agree that civil disobedience has an honourable history in the UK, and should the court take the conscientious motives of the protesters into consideration when sentencing?

The example that we always give is the suffragettes, who at the time, used methods of direct action. They used methods, which today, we would think were quite extreme. And yet now we look back and we say, That was legitimate, they were asking for votes for women. So, yh I think direct action and civil disobedience, is a tactics which has been used in the UK, in the past. As to whether the courts should exercise restraint, I agree with that. What we're seeing at the moment is that judges are not acting with restraint and I'm not taking the fact that these are protest cases into account.

Have you ever attended a protest in the past, where your demands were met, and what methods of protest did you employ?

The first protest that I attended was the march against the Iraq war in 2003 when I was a student. Um, and so, no, the demands for that protest were not met. It was just millions of us marching through the streets of London. I continue to attend protests.

Interview with Lawyer Katy Watts

Can you please introduce yourself?

I'm Katy Watts. I'm a solicitor at Liberty. We are a campaigning organization which tries to safeguard and promote human rights through a mix of campaigning work, policy work, lobbying, and strategic litigation. Protecting the right to protest has been a big focus of our work over the last four years.

Why is this an area of focus?

In the last three years, we've seen a huge swathe of anti-protest legislation. Until a couple of years ago, the main piece of legislation was the 1986 Public Order Act, which gave the police powers to control and limit protests in certain circumstances. It served as the main source of protest-related criminal offences. In the last three we've seen, the Police Crime Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, which was immediately followed by the Public Order Act 2023 - and both have handed the police, vast new powers to, place limits and controls on protests.

The Public Order Act 2023 introduced two new offences - called locking-on and tunnelling. What amounts to an offence of locking-on or tunnelling?

Essentially, locking-on amounts to attaching yourself to an object or land. It's an offence designed, I think to target the kind of increasingly creative methods that environmental protesters use. to draw attention to their cause. So it's an incredibly broad offence, which is designed to target people using what are very legitimate protest tactics, like attaching yourself to buildings. We'd seen those tactics used by suffragettes, locking yourself to something is an established means of direct action. Tunnelling similarly, was targeted at the kinds of methods being used by environmental protesters to like tunnel under construction works, including HS2. I think probably we have fewer concerns about that as a method of protest.

In 2023 the government sought to expand the definition of “serious disruption” as mentioned in the Public Order Act of 1986, but the amendment was not pursued and the House of Lords rejected it - what would have been the impact of this amendment?

We know what the impact was. The amendment would have lowered the threshold for when the police can interfere. in a protest. For example, limiting the number of people, dictating the location, the route of a march, the time of a protest, and the overall impact of a protest - previously this sort of authority could only happen if the police reasonably believed that there would be serious disruption. The Lords voted it down, partly because they didn't have time to adequately scrutinise it, so it fell away from the bill. What happened next was that the government, having failed to change that definition the first time - brought in secondary legislation to amend the Act - using its executive powers which by itself is not primary legislation. So, we know what the impact is because they brought it in. The amendment which has been enforced for a year now, lowers the threshold from serious to more than minor disruption. Meaning any protest likely to have a more than minor impact on the local area, could be subject to limits by the police.

Liberty has brought a case against the government - on what basis exactly? Well, we’ve challenged that decision on the basis that the government did not have the power to use secondary legislation in that way. The executive power they used, granted them the right to kind of clarify the meaning of serious disruption, and to provide examples of what serious might mean, but it didn't allow them the power to lower the threshold. The court in May of this year agreed with us, said the government had gone too far, and so found that the decision was unlawful. However, the regulations remain in force and the court is hearing the government's appeal on Tuesday [23rd July 2024].

As UK citizens do we have an inalienable right to protest, or is it subject to law and change? The right to protest is guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, articles 11 and 12, which is incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act. It guarantees us the right to free expression and to meet and to gather. Under the European convention, the right to free expression doesn't just include speech, it goes further and includes expressive acts - like acts of protest. They are not absolute, they can be subject to limitations. So if there is going to be serious disruption arising from a protest, then, it's open to the government to place some kind of limit. But it has to fall under the category of serious disruption, not just more than minor. It gets more complicated when, we're talking about direct action and what might, potentially amount to a violent protest - but what's happening, currently, is police have been given the powers to act broadly and more preemptively, and situations were drawing attention to issues like climate change by blocking roads or interfering with motorways, would lead to the criminalization of protesters - when on a balance, that is the nature of the protest, for it to be a bit disruptive, otherwise, nobody notices it.

The Sentencing of Roger Hallam

“ You could hear them inside banging the walls of the van - people found that moving.”

John, 72. Protester. Member of Justop Oil. Retiree.

Just stop oil members; Roger Hallam, 58, from Wales. Daniel Shaw, 38, from Northampton. Louise Lancaster, 58, from Cambridge. Lucia De Abreu, 35, from Derby. and Cressida Gethin, 22, from Hereford. Five of them were put on trial for conspiracy to intentionally cause a public nuisance. It is rumoured that a Sun newspaper journalist joined a Zoom call under the guise of being a fellow JSO supporter, and recorded the meeting. The recording was used as irrefutable evidence of the 5 of their involvement in a Direct Action that took place back in 2022.

The scale of that direct action in November 2022, metropolitan police say affected over 700,000 vehicles and caused more than 50,000 hours of vehicle delays. Groups of JSO supporters scaled the gantries along the M25, in over 13 different locations along the road, Metropolitan police arrested 23 people over two days - some, while still on their way to the gantries.

That was in 2022. Today's trial and ultimate sentencing, if for the 5 said to have conspired to cause that disruptive event. Outside the courtroom, I spoke with protesters waiting to show support as the prison van arrived and left the same way.

John, one of the protesters waiting patiently, spoke with me about his transition from Clinical Biochemist to rebel with a cause. He said, “When you decide to get disruptive, do you tell your friends, do they suddenly think you're stupid, I had to decide who to tell and who not to tell”.

John expressed to me the concern that family and friends have about him engaging in this sort of direct action.

But he ended by saying, “If you just explain to the people closest to you, even if they don't feel the same urgency as you, they'll try and support”.

Addie, a different protester - came here to Southwark Crown Court, from Devon. Says she's been involved in direct action and has been arrested almost eleven times for it. As per her probation, she must make it to London every other week. When asked about her mood in relation to the sentencing she said; “everyone is feeling the pressure, everyone is feeling angry and scared”.

Judge Christopher Hehir, sentenced all five of them to prison time. Roger Hallam, after being doubly tried for contempt was sentenced to 5 years. Roger Hallam is the co-founder of Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion.

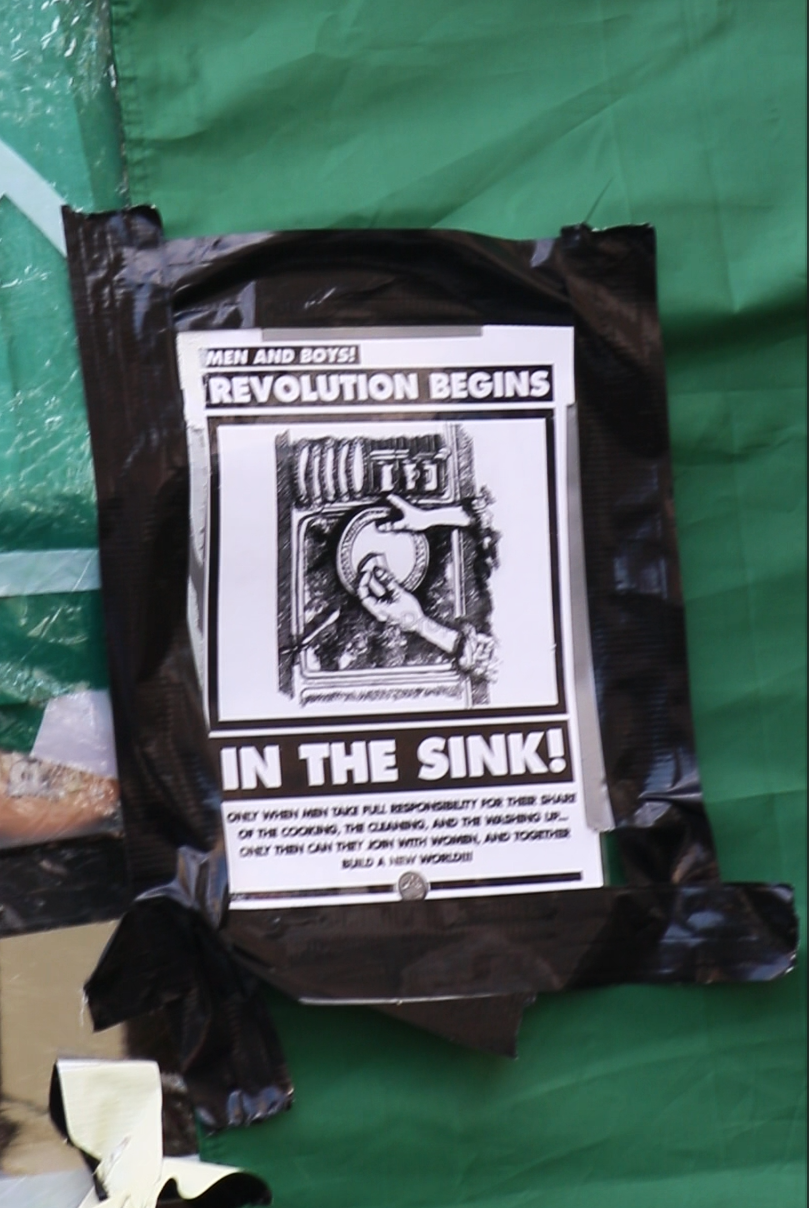

Making wheat paste. Youth Demand Social Evening | Original image taken by Dan Eboka

Making wheat paste. Youth Demand Social Evening | Original image taken by Dan Eboka

Soup Night at Youth Demand

“I heard of youth demand through my friend’s friend, who I've always looked at as so cool - because she gets involved in so many things - she was my final push to finally do something.”

Aliza, 21. Member of Youth Demand. Student at Goldsmith.

Founded in January 2024, the group Youth Demand is relatively new to the campaigning scene. They are branded in the guardian and spectator as one of several subgroups founded by JSO members. But speaking to one of its members at a social evening, and he was clear that the group was separate - unique in its own campaign identity. And they very well are - unique. Different from Just Stop Oil - in the sense that the groups itinerary is twofold. To put pressure on UK government and to reduce the production and increase of fossil fuel - and also to use the same political technique to influence a UK arms embargo on Israel.

Only five months old and already, some of its members have similar stories of being involved in Direct action and subsequent police arrests. Aliza, a former member of JSO, joined Youth Demand in March. She spoke about the conversations she and her friends would have before joining. Conversations about climate change - and even more pertinent ones about social inequalities at large.

According to her, these conversations partly influenced her decision to join - but in retrospect, she remembers always being sort of aware, she says; “..Both my parents worked in jobs where it meant we were exposed to unfairness in different people's lives. I never wanted my decisions to force me into that way of living.” Aliza has been involved in some slow marches and has been arrested twice. She describes not wanting to feel any anger towards the police; “I understand they come in thinking something bad is going to happen. But watching your friends getting dragged off - and then waiting, knowing you're next..”

A Retrospective

The earliest report of a civilian riot in a democratically elected system was Shays' rebellion In america. Rural farmers in Massachusetts demanded lower taxes and better economic policies in the face of high taxes and aggressive debt collection. The result was year-long armed combat with the military, the loss of civilian life and the demands were never met. A riot is by far the most violent and poses a clearer threat to health and safety. Also, the response is by far the most predictable. Since the rioters have passed the realm of peaceful protests and passed the realm of being communicated with - the state feels justified to respond with immediate and direct force. By this critique, it's hard for a protest movement to sustain itself on riots alone. And here comes the unenviable role of a figurehead or figureheads - in the life of a protest movement. Shay’s rebellion is named after Shay Daniel, a wealthy army man, turned farmer.

“Sometimes the role of a figurehead is important, it may partly depend on the age or stage of the campaign. (Early on things can be wider, more open.) It can also depend on the politics of those involved: feminist or anarchist informed activisms may seek less central authority in their actions. But it’s also an external media pressure: for instance, journalists will look for and may remember the activist who can articulate best, most clearly and succinctly.”

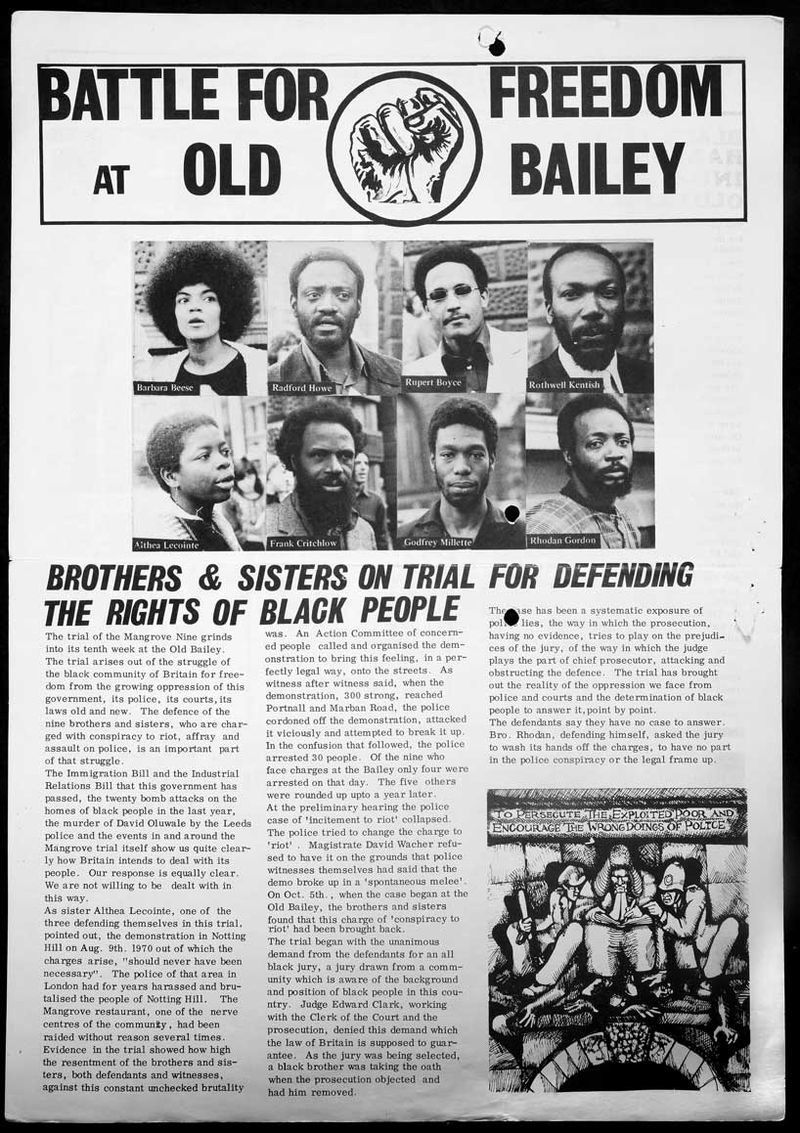

A riot over a restaurant: Story of the Mangrove 9

The Mangrove 9 were a group of black British activists part of the Black liberation movement in the 60’s. Nine of them were tried for inciting a riot at a protest against police harassment.

The Mangrove Restaurant in Notting Hill, London, was a Caribbean restaurant, owned by Frank Crichlow. It was also one of the many meeting points and hubs for the Black community and activist movement in that part of London. It was frequently raided by police. According to the national archives, the restaurant was been visited by the police 12 times over a period of 18 months. The allegations were for criminal activity and drugs. However, it is said that no evidence was found during the raid. On August 9, 1970, around 150 people marched from the Restaurant to protest in front of police stations around the area.

The match was halted, by police and violence broke out. Frank Crichlow Darcus Howe, Althea Jones-LeCointe, Rhodan Gordon, Rupert Boyce, Anthony Innis, Rothwell Kentish, Godfrey Millet and Barbara Beese - all nine activists were arrested and charged with inciting a riot. The trial lasted 55 days and gained public attention. Two out of the nine chose to represent themselves as lawyers in the court. In a statement from the trial judge, he says there was “... regrettably evidence of racial hatred on both sides.” - according to the National Archive - this quote is the first judicial acknowledgement of racial prejudice in relation to the Metropolitan Police.

Article 1.2 Interview with Jamila Bolton Gordon.

Jamila at the site of the former mangrove restaurant. Original Photo Taken by Dan Eboka

Jamila at the site of the former mangrove restaurant. Original Photo Taken by Dan Eboka

Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Jamila Bolton Gordon. I'm the daughter of Rodan Gordon who found himself as part of the Mangrove Nine in 1970.

Growing up how did you learn about the trial that your father was involved in?

Um, internally from my mum. Not from my dad. Um, I equate my dad to, uh, a soldier who came back from war and didn't talk about his, challenges to do with the police, and the system of brutality he faced. So, we carried on as normal, as father and daughter, because he had businesses that I was helping him to run. I noticed he was popular. I knew he was a community developer. But I didn't know much about the Mangrove Nine, per se. It's only really once I moved away, finished my studies, and started having children, that I started to revisit the history of my dad. But by that time my dad wasn’t as active anymore. He had some health challenges around his mid-50s, and closed down all his charitable businesses - so I refocused myself on helping to sort out the family business back home. We didn't get into the Mangrove Nine, unfortunately, until he passed away. Growing up I always noticed the love that other people had for him but it was foreign to me. It was a filmmaker and a historian in the grove called Ishmael, who understood the significance of his story more so than I did. So because of Ishmael, to some extent, and others, I thought, well, let me start digging into the story after he had passed.

What did you find, while revisiting?

He was already part of a revolution in Grenada. In 1954, the workers took strike action against the plantation owners. Back then my dad had his own paper called Backyard and used to cover the stories.

So he was a publisher?

Uhh, my dad was something of an orator - a connector. A community development worker, so he could see that there was a need for something, and then he would find out what people could he gather to match that need. In other words an activist. My grandmother had sent him to Trinidad to study theology - then it was either you beacme where a farmer or a priest. But Dad skipped taking his vows because he said it because he liked women too much! [She breaks into laughter]. So he definitely wasn't going to be a priest. But he [00:13:00] learned through the uprising of the plantation workers. And how his brothers dealt with, um, the ideology of, um, uplifting the workers, giving them a salary that's decent, but also health and safety. So he was very, um, aware of those issues. My dad turned 32 tight around the mangrove trial - myself I had turned,... by the time I started researching about him.

Did learning about his story change how you saw him?

I was very proud of him, but also, um, a bit disappointed - because people will make up their versions of what they think he did or didn't do - I had wanted to hear about it clearly from him, why did certain people in the community dislike my him because of his stance and his principles. It's an area where you feel like a fetus, in a womb, where so much is going on around you, but you don't understand it. But then the point of pride I have now is because I feel what he and the others developed was, and is generational. It kind of pacified the side of me that didn't have my dad - because he gave so much to the community.

What do you think the lasting impact was, of the mangrove trial?

Our parents went to war with the state and the impact on their families was generational. For the broader community, the trial set a legal precedent. The judge confirmed that what our parents knew already was true, that there were elements of racial discrimination in the policing system. But we knew that already. In a way, the impact was less grand than you'd expect. It just cleared their faces in the eyes of people who never gave them the benefit of the doubt. The real impact for me wasn't the trial, but the community they built. They contributed all their time and effort to developing black neighbourhoods in the Notting Hill area. Around that time between 1968 and 1970, we had a lot of housing issues, we had employment issues, we had social services issues, we had educational issues and financial issues - and then you had places like the Kensington Law Center, the Harrow Road Law Center, and BPIC [Black People's Information Centre] which my dad and members from the nine help run. It was an information hub essentially so you knew where to go, what rights to have, who to talk to about a loan and the rest. The restaurant was an extension of that.

What do you think protest movements today - groups like Black Lives Matter - can learn from your dad's story?

If your going to spend a lot of time fighting pick your adversaries well but more importantly your community of supporters well. The nine of them stuck together merely out of survival, but they also knew the community they were fighting for, more importantly, they had helped to build that community. Also, you need to know the law and study the rules they are charging you under - if you know it well they can't use it against you. It's no coincidence that some of the mangroves took the option to defend themselves in court.

8 All Saints Road in Notting Hill, West London, England. The original site of the Mangrove restaurant, now a cocktail bar | Original photo taken by Dan Eboka.

8 All Saints Road in Notting Hill, West London, England. The original site of the Mangrove restaurant, now a cocktail bar | Original photo taken by Dan Eboka.